“Neither Anti-Negro Nor Anti-Semitic”

On Oregon Road: Robeson and the politics of forgetting

“…the [concert] was held deliberately to create an incident or breach of the peace.”

-John A. Gaffney, State Police Superintendent

“Our objective was to prevent the Paul Robeson concert and I think our objective was reached. Anything that happened after the organized demonstration was dispersed was entirely up to the individual citizens and should not be blamed on the patriotic organizations.”

-Milton Flynt, Commander of American Legion Post 274

“Each summer the year-round population of this region is augmented by large numbers of summer residents and vacationists. […] A large majority of these people come from New York City. […] There are active minorities of Communists and Communist sympathizers in some of these ‘colonies.’”

“…made the usual Communist attempt to ally the Party with Negroes and Jews as the likely victim ‘if the Fascist-inspired pro-war forces win.’”

“The Grand Jury is convinced that the violence […] was basically neither anti-Semitic nor anti-Negro in character.”

-Presentment of the October 1949 Grand Jury of Westchester County

I hate, I despise your festivals,

⠀and I take no delight in your solemn assemblies.Even though you offer me your burnt offerings and grain offerings,

⠀I will not accept them,

and the offerings of well-being of your fatted animals

⠀I will not look upon.Take away from me the noise of your songs;

⠀I will not listen to the melody of your harps.But let justice roll down like water

⠀and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.

-Amos 5:21–24 (NRSVue)

For now, it’s just a traffic jam with inconvenient timing.

The sun’s shining over the Highlands, casting a warm glow over a line of cars and charter buses. State troopers direct traffic north, and in doing so usher them into the kill zone. Ahead and to the side, war heroes stand in partial uniform. A crude effigy of the most famous Black man in America— perhaps only contested by Jackie Robinson— hangs by the neck from the hook of a tow truck.

Housewives have packed for a picnic, not a pogrom. They’ve brought lawn chairs and Thermoses and sandwiches wrapped in wax paper. Children sit on the hoods of Chevys and Fords, legs swinging— half-bored, half-thrilled— watching the neat, single-file line of “outsiders” snake closer.

They’re not here to glare.

In the back seats, other children are still clutching concert pamphlets, stiff paper gone soft at the corners from nervous fingers. They don’t see the first rock leave a wicker basket curbside. They hear it: a sharp, hollow crack as it meets glass, then the explosive bloom of their windshield giving way. Shards spray the front row, breaching skin, muscle, and eye. On the shoulder red, white, and blue banners snap in the evening breeze, bright and emphatic, in case it wasn’t clear which side belongs to God.

All of this was— of course, entirely predictable. In fact, just down the road a week before, it had— we are at the second concert, the one organized in defiance of the riot that prevented the first one. The police will watch. The victims will be blamed.

If you pull the camera back, we are not in Birmingham or Selma, not some sticky Mississippi Delta nightmare we’ve safely tacked to a different region and a different kind of white person. It’s Westchester County, the Empire State Building visible from the crests of hiking trails on a clear day, where you can now buy Paul Robeson’s biography in a cozy indie bookstore and then drive the road where they dragged people from their cars for daring to hear him sing.

There is much more to this story than a small-town concert— there’s the man who performed, the two crowds that converged— twice, and the river town that tried very hard to forget what it did. It’s also a story about what we inherit from that dissonance.

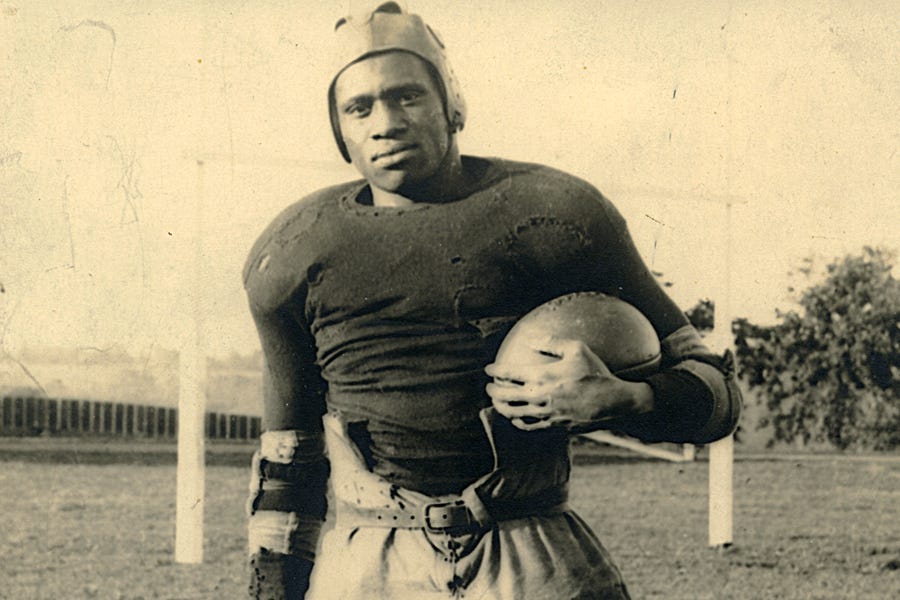

We start with Paul Robeson: the great boogeyman of this story. “Renaissance man” is the phrase you reach for when your brain would rather itemize his talents than face what was done to him: living proof that a Black man could master every field this country claims to revere— football, law, acting, music, politics— and still be denied belonging.

He was born in Princeton, New Jersey in 1898, to the Reverend William Robeson, who had escaped slavery in North Carolina and Louisa Bustill Robeson, from Philadelphia’s Bustill clan— part of the city’s small free Black elite. His mother died in a freak accident when he was five. Princeton at this point was a town of contradiction: one of the larger Black populations in the North, about 18%, and also a mecca of reactionary academia: where architects of poison like Woodrow Wilson would shift public perception of the Civil War decidedly towards the Confederacy. Princeton would not regularly admit Black students until the 1940s.

A pastor’s son, Paul grew up at the mercy of his father’s calling. When the elder Robeson’s sermons on social justice made him unwelcome in a given pulpit, the family packed up and pivoted to another. His formative years would be spent in Somerville. He was not merely a model student at Somerville High: he was in the glee club, drama club, played multiple sports (especially football), and was obsessed with debate and public speaking. He graduated as valedictorian and that combination— grades and that unquantifiable but very perceptible star power— earned him a scholarship to be the third Black student to ever attend Rutgers.

His reception at Rutgers was exactly what you’d expect. White teammates on the football team tried to terrorize him off the team. He was kept out of the glee club because he couldn’t attend the white’s-only functions where they performed. His father became deathly ill and Paul became his primary caretaker. He stayed anyway. By the time he left, he’d piled varsity letters, been named All-American twice on the field, been tapped for both Phi Beta Kappa and Cap and Skull, and was elected class valedictorian. On graduation, he gave a thunderous oration imploring his almost entirely white classmates to “clasp friendly hands” and work towards the goal of equality regardless of race. It’s safe to say he’d made his point.

He lands where you’d expect for a young Black striver with an intellectual knack and something to prove: Harlem. The Harlem Renaissance is in bloom, and Robeson throws himself into it while he grinds through Columbia Law. He steps away from school to start acting— first onstage, then on the silver screen— and earns critical acclaim in The Emperor Jones. When he’s used up all his leave, he somehow manages to juggle reading law with playing in the NFL for two seasons, graduating in 1923. He tours internationally, including appearing in the London productions of Othello and the musical Show Boat, as well as the Swiss experimental film Borderline.

As his fame grew, so did the pressure to not rock the boat— to be outwardly grateful, decorous, apolitical. Robeson refused that façade. Walking home during a Rhondda Valley lockout, he ran into a choir of Welsh miners protesting in London and joined their singing— spontaneous, uncalculated, the polar opposite of the expectations of a Black star. He returned to Wales repeatedly to sing for the miners, and even after the U.S. government revoked his passport, he sang to them decades later by telephone.

His politics also put him on a collision course with the anti-Communist consensus hardening around him. On a visit to Stalin’s Moscow, he famously said “here I am not a Negro but a human being for the first time in my life.” And in a Berlin train station en route, his wife Essie later recalled being confronted by Nazi brownshirts, disturbed by the sight of his lighter-skinned wife beside him. In a world drawing its lines in bolder and bolder ink, Robeson kept stepping over them.

As the common enemy of fascism rose, he threw himself also into that fight. A self-declared “citizen of the world,” he came to Spain to sing to the International Brigades. He turned up in the S.S.’s Sonderfahndungsliste G.B.— the black book of who to arrest if Britain fell.

Back in the United States, he fought on the home front: sang at military bases, headlined war-bond rallies— all while insisting the war against fascism meant nothing without a war against segregation at home. And for a few summers after— 1946, 1947, 1948— he sang in the Peekskill area without incident. Things would change by 1949.

That spring in Paris— with the Berlin Airlift still underway— Robeson took the stage at a Soviet-organized peace conference at the Salle Pleyel. He sang “Joe Hill,” the ballad of a Wobbly labor organizer railroaded into a murder conviction and executed by firing squad in Utah. He spoke off the cuff, as he was often to do, about Black life in America and the lunacy of potentially sleepwalking into another war. Before he spoke however, the Associated Press had somehow already wired his remarks back to Rockefeller Plaza: attributing to him language he hadn’t used, a comparison of American policy to that of Hitler and Goebbels, and a claim that Black Americans would support the Soviet Union in a war against the United States. It was completely false, but that was no matter.

It detonated perfectly with an American public already on edge. It created a firestorm in the press, and soon Congress was doing what Congress does. House Un-American Activities Committee chair John Wood subpoenaed Jackie Robinson to denounce Robeson’s speech— even liberal darling Eleanor Roosevelt used her column to scold him. And by the lead-up to the next summer concert in the vicinity of Peekskill, the editorials in the local nightly preordained what was to come:

It appears that Peekskill is to be “treated” to another concert visit by Paul Robeson, renowned Negro baritone.

Time was when the honor would have been ours— all ours. As things stand today, like most folks who put America first, we’re a little doubtful of that “honor,” finding the luster in the once illustrious name of Paul Robeson now almost hidden by political tarnish.

Paul Robeson rose to preeminence as an American artist on stage and radio, and was applauded by an America that was oblivious to his color. In spite of modest background, he rose with highest academic honors through our college system, and was chosen an all-American football star.

His magnificent voice, which thrilled millions, opened up a brilliant career for him that easily could have led to a place in the halls of American fame. His influence with his people, properly directed, could have won a place for him beside Booker T. Washington and George Washington Carver, as truly great Negro Americans.

Any possibility of such attainment is now, in the opinion of most Americans, lost to him forever.

The local concert will be held this coming Saturday at the Lakeland Acres Picnic Grounds. The singer is being represented by the People’s Artists “for the benefit of the Harlem Chapter, Civil Rights Congress,” according to posters appearing in the neighborhood.

Inasmuch as the Civil Rights Congress has been cited as “subversive and Communist” by Attorney General Tom Clark, and has been referred to by the Congressional Committee on Un-American Activities as being “dedicated not to the broader issues of civil liberties, but specifically to the defense of individual Communists and the Communist Party,” it becomes evident that every ticket purchased to the Peekskill concert will drop nickels and dimes in the till basket of an Un-American political organization.

If the Robeson “concert” this Saturday follows the pattern of its predecessors, it will consist of an unsavory mixture of song and political talk by one who has described Russia as his “second motherland,” and who has avowed “the greatest contempt for the democratic press,”

The time for tolerant silence that signifies approval is running out. Peekskill wants no rallies that support iron curtains, concentration camps, blockades and NKVD’s, no matter how masterful the decor, nor how sweet the music.

-Unsigned editorial titled “The Discordant Note” written by E. Joe Albertson, editor — The Peekskill Evening Star, August 23rd, 1949

Robeson was a marked man.

The first time I came to Cortlandt for this story was an accident. It was early December. We were driving back from a weekend in Vermont— an escape for a few burned-out Zohran staff and volunteers, huddled into a rental car bound for LaGuardia, I insisted the Taconic would be faster than I-91. That’s where I went to high school. That’s the 110-degree hell-exit onto Mountain Road I had to merge across when I was sixteen. At some point someone had to pee and perfect— there’s a public bathroom where Main Street abuts the Metro-North tracks in Cold Spring.

The GPS recalculates. Bear Mountain Bridge, then the Palisades? Cut across the George Washington Bridge to the Triborough? An excellent way to get fleeced. No— 202 to Route 9 and the soup of parkways in southern Westchester I know exist but can’t describe.

It was a particularly frigid day: snow on the ground, dusk haze— few commonalities with the summer of ‘49. But if you’ve never driven here, it’s a real treat. Coming from Garrison on 9D, you pass thigh-high, crude stone walls that once separated farms— land that reforested generations ago. Carrying on, the road arcs towards the river, teasing you with brief glimpses of what is to come through the tree line.

Then, almost immediately after the Town of Cortlandt sign, the trees fall away and the whole scene appears at once: only feet ahead road transforms into the deck of the Bear Mountain Bridge— for a hot minute in the mid-1920s, the longest suspension bridge in the world— and the ancient Hudson Highlands behind it. Anthony’s Nose is flush against the road; Bear Mountain sits across the river. Only then do you register the height: a 400-foot drop, held back by newer, properly cemented stone walls. A poor man’s Big Sur, climbing as it winds toward Peekskill.

Cortlandt is one of those municipalities that doesn’t read like a cohesive place so much as a rectangle drawn around one: it awkwardly encircles Peekskill— part of Cortlandt until 1940. Keep going south along the old Albany Post Road and Cortlandt reasserts itself— past industrial Buchanan, Verplanck, and Montrose, then through wealthier Croton-on-Hudson. Just shy of 43,000 people live in Cortlandt now— more than in Peekskill— though the number was closer to 18,000 in 1949.

At this point, the illusion created by the state parks of untouched wilderness has imploded into the bedroom communities of Westchester. This was less the case in 1949, though the Peekskill area was changing quite a bit: already 600 weekday commuters to the city (estimates suggest a peak just before COVID of around 7,600).

But the weekday commute was only one version of this relationship. In summer, the population spiked by about 30,000— and that “seasonal” influx wasn’t the tidy commuter class postwar Westchester would later flatter itself with. It was Jewish New Yorkers hardscrabbling their way into the lower middle class: renting bungalows, sharing the lakes and the roads, building little worlds that were— by some affectionately, by some not— called “colonies.”

To the townies, the difference didn’t just exist; it could be policed. They heard it in Yiddish accents and surnames, in their dress and ritual, in their conflicting perspectives on if and how to “Americanize,” in where and how they prayed. And because many were utopian without shame (some colonies were associated with different communist and anarchist movements, and the erstwhile American Labor Party had a local chapter since conception in the 1930s)— these communities became suspect by default in the paranoid vernacular of the time: not just places people went, but places ideas circulated. In their minds, a contagion risk. What started as children’s camps and summer escapes ossified into something more permanent: a presence that locals could not pretend not to see, and could not stop trying to classify. “No Hebrews” began slipping into local business ads and deed covenants.

It also obscured a deeper truth: Jews already lived here— a handful of Sephardi families dating to New Netherland and a larger group steeped in a Conservative congregation anchored enough to bury their dead along Hillside Avenue. But in the townie imagination, Jewishness was increasingly not allowed to coexist with “local.” It meant outsider, and once the Cold War tightened public consciousness, it meant “Red” as well.

Sensing the rising tension leading up to the concert, a local civil rights activist, Victor Sharrow of Crompound, sent a telegram to the state Attorney General Nathaniel Goldstein:

This is an urgent telegram in reference to a lead article on page one, a lead editorial, and a letter to the editor on page four of the Peekskill, N.Y., Evening Star of Tuesday, August 23, 1949, concerning a “Summer Musicale” [sic] sponsored by the “Peoples [sic] Artists,” Paul Robeson, guest artist. The tone of the combined articles are to do “something” to see to it that this affair is disrupted or to see that it’s not carried out in a peaceful manner.

As an individual, and Chairman of the Crompound Branch of the American Labor Party, I am writing to you as Attorney General of the State of New York, to use your office, to see that this affair, contracted for to occur at the Lakeland Picnic Grounds, Hillside Avenue, Peekskill, N.Y., Saturday, August 27th, 1949, 8 P.M. is held, and held peacefully. A letter with the enclosed articles follows.

How is it that we have this correspondence? Seemingly someone at either the telegram office or the Attorney General’s office leaked it to the Evening Star, which published it along with Sharrow’s name and where he lived the next day. When asked for comment, Assistant Attorney General Kent Brown acknowledged it had been received, and that as of then the Attorney General’s office did not intend to take any action to protect the concert.

I get to Peekskill the same way Robeson arrived that August night: by train from Grand Central, though I step off into a very different Peekskill than he did. Peekskill today is 46.2% Hispanic, 31.9% White, and 18.7% Black. In other words, whatever story you inferred about “a small white river town”— the present doesn’t cooperate.

But Peekskill does have many of the small things small river towns all have. A Main Street begging to be walked. Foursquares and big apartment buildings dotting the hills. A municipal instinct to turn a brush with a famous man into a permanent civic asset.

Here, the famous man is Abraham Lincoln.

A brief stop by the president-elect at the local freight depot as his inaugural train made its way to Washington has rendered the place a museum to him, restored as the Lincoln Depot Museum. He pulled in at 2:00 p.m. on February 19th, 1861, stepped onto a baggage cart that would be his impromptu podium, spoke four sentences, and left.

I don’t mean to be too snide. It’s actually kind of sweet. It’s also revealing.

Robeson had called ahead from Grand Central to a friend, Helen Rosen, to relay he had heard there may be trouble at that night’s concert. They decided instead of him taking a taxi to the concert as planned, she would ask some friends in Yorktown (her car was apparently too shoddy for the task) to deliver him to the concert grounds. Apparently, there was no cause for concern by the station that day. That decision may have saved his life. The riot had already started.

I begin my walk to Oregon Road.

There were two concert grounds: the concert on August 27th was at the Lakeland Acres picnic area— now the Hollow Brook Golf Club. The second, rescheduled, defiant concert was on September 4th at confusingly, the overgrown Hollow Brook Country Club, now a small stretch of single-family homes about half a mile further up the road.

Even then, the place was already being rewritten. Westchester’s postwar sprawl was laying its outer ring around Peekskill: new roads, new plats, new setbacks, the slow suburban reflex to pave over anything that didn’t fit the brochure.

The riots landed in a place mid-transition: not yet polished manicured suburbia, no longer the old river town hinterland. Roads were being pushed outward, houses multiplying, and yet even today there remain some stubborn patches of trees along the path.

Cross into Cortlandt and the signage changes: North Division Street becomes Oregon Road, and sidewalks start becoming optional. The riot’s geography is trapped in that aforementioned administrative weirdness— Peekskill’s name is on the tin, but the violence was confined to the Town of Cortlandt.

Shortly after the town border, I deviated to the Cortlandt Town Hall for a bureaucratic errand. I was born here— though like many, I’d long confused the municipality of record with Peekskill itself. I used to resent that.

I grew up across from the shuttered, though not yet demolished Julia L. Butterfield Hospital in Cold Spring, the one that might’ve delivered me if it had held on nine more years. My mother had to choose between two hospitals: Vassar Brothers in Poughkeepsie— the working-class city where she and my grandparents lived, worked, and later, so did I— and Hudson Valley Hospital in “Cortlandt Manor”— Westchesterese for “not Peekskill.” The latter won.

To me, Cortlandt was never anything but distant, tony Westchester: a place where my mother drove, bleary-eyed, at 5:30 a.m., to earn a wage she could raise two children on, a place I only saw from the train between my two worlds or occasionally, where I needed to transfer when I mindlessly boarded an electric train instead of diesel. It never felt like mine, certainly never made narrative sense. Today as I walk the hollowed-out streets of Verplanck and Buchanan, past the skeleton of Indian Point, across the traffic circle on Oregon Road— once Hillside Avenue, renamed after the headlines, as if renaming could erase it— where the sidewalk disappears into snow and ice, where a crime passed for security and silence passed for justice: it feels... closer.

On the same page as “The Discordant Note”— buffered by a letter from Mrs. A.S. Keith denouncing the local school board’s decision to scrap their core curriculum for encouraging “anti-American ideals” in middle schoolers— was a letter to the editor on Robeson’s impending concert, this one signed:

August 18, 1949

Editor,

The Evening Star

Peekskill, N.Y.

Dear Sir,

The present days seem to be crucial ones for the residents of this area with the present epidemic of polio. Now we are being plagued with another, namely the appearance of Paul Robeson and his Communistic followers due to appear here August 27th. It is an epidemic because they are coming here to induce others to join their … [sic] ranks and it is unfortunate that some of the weaker minded are susceptible to their fallacious teachings unless something is done by the loyal Americans of this area.

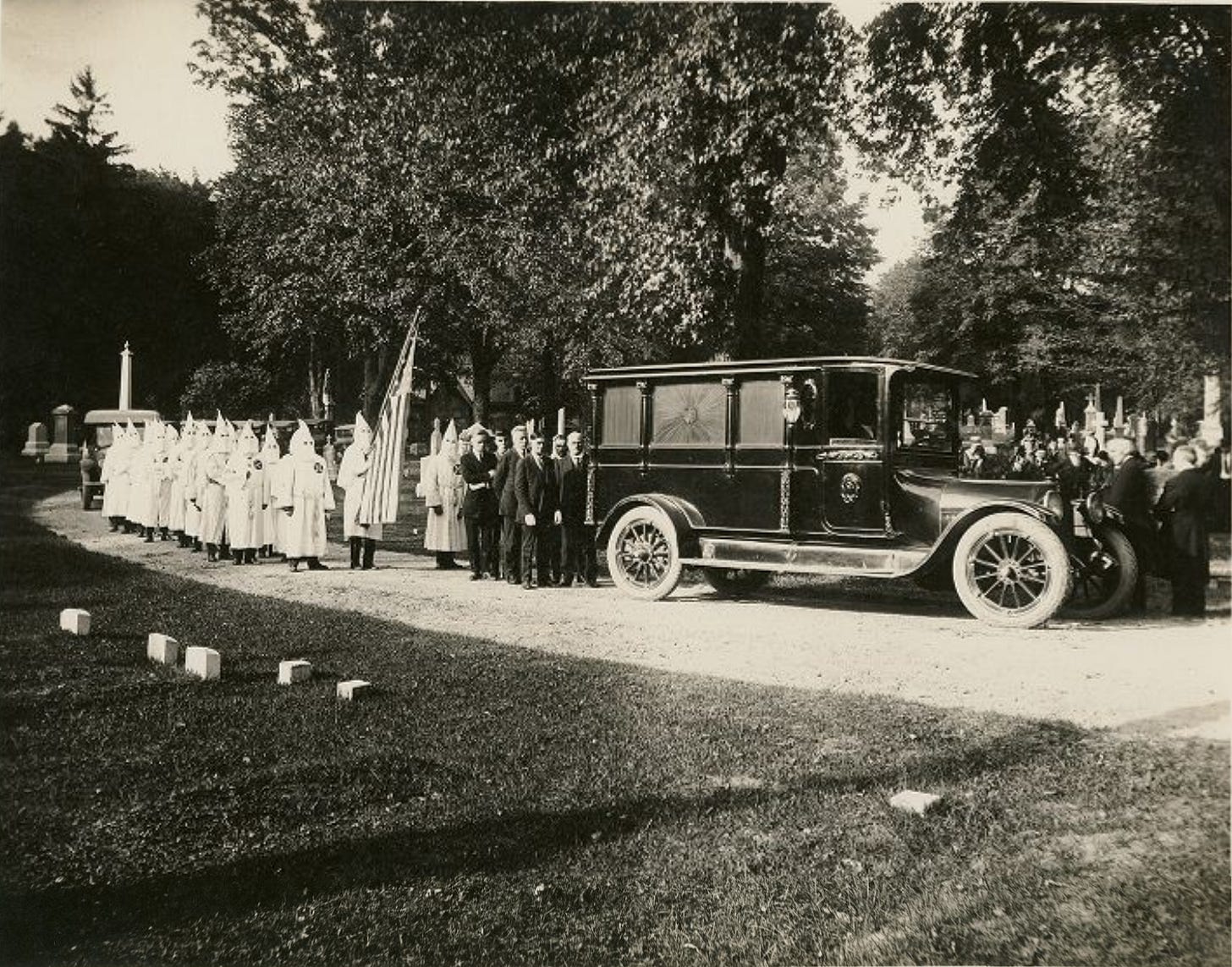

Quite a few years ago a similar organization, the Klu Klux Klan, [sic] appeared in Verplanck and received their just reward. Needless to say I am not intimidating violence in this case, but I believe that we should give this matter serious consideration and strive to find a remedy that will cope with the situation the same way as Verplanck and with the same result that they will never reappear in this area.

The irony of this meeting is that they intend to appear at Lakeland Acres Picnic Area. If you are familiar with this location you will find that it is located directly across the street from the Hillside and Assumption Cemeteries. Yes, directly across the street from the resting place of those men who paid the supreme sacrifice in order to insure [sic] our democratic form of government.

Are we, as loyal Americans, going to forget these men and the principles they died for or are we going to follow their beliefs and rid ourselves of the subversive organization? America, in general, seems to have forgotten the past war and its sacrifices but if we tolerate organizations such as this we are apt to face a repetition of the past and in the near future.

If we, of this area, have not forgotten the war, then let us cooperate with the American Legion and similar veteran organizations and vehemently oppose their appearance or reappearances. Let us leave no doubt in their minds that they are unwelcome around here either now or in the future.

So far no action has been taken by organizations or individuals in opposition to this rally but I trust that it will be properly acted upon by the proper organizations or authorities.

Sincerely yours,

Vincent Boyle

-Letter to the Editor — The Peekskill Evening Star, August 23rd, 1949

Boyle’s letter in many ways speaks for itself, but also invokes an older memory worth delving into. Peekskill by this point was about one third Catholic, Catholics who along with their Jewish and Black neighbors only two decades ago had been terrorized by another form of “America first:” the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.

In the river towns of the Lower Hudson Valley, the Klan is not a distant Southern punchline. It was the Second Klan of the 1920s: a mass fraternal movement that operated locally as a civic institution— something like an Elks Lodge with a racial and religious covenant— fueled by the national popularity of The Birth of a Nation and bound together by whiteness, Protestantism, and the determination to police who belonged in a changing America. These were business owners and shopkeepers, men with social standing and political sway. They lost. They were beaten back by local alliances— churches, veterans, neighbors— deciding, explicitly, that the Klan was not welcome.

That history matters not because Boyle is making an astute comparison— he isn’t— but because he is relying on a shared local shorthand: the Klan as the last time the community had to decide who belonged, who didn’t, and what form of “opposition” counted as legitimate. The record of that earlier fight is still visible in the region’s newspapers, parish life, and political memory: a period when “patriotism” and intimidation also travelled together, and when defeating the Klan required a counter-coalition sturdy enough to deny it oxygen.

The irony is that, with that fight still within living memory, the lines of the next battle were merely drawn to include more in their ranks. Along with the American Legion, Veterans of Foreign Wars, and Catholic Veterans— the Westchester County Jewish War Veterans were also among the organizations that helped form the anti-Robeson mob.

Coming to the site of the first concert, it is immediately apparent why it was chosen. It’s a hollow: a shallow, bowl-shaped divot in the landscape, one that the novelist Howard Fast— reluctant lead organizer of the first concert, author of the most detailed account of the riot— recalls as a physical trap:

To understand what happened from here on, you must have in your mind a clear picture of Lakeland Picnic Grounds and of the area where the concert was set up. The entrance to the grounds is a left turn off the main road as you drive from Peekskill; the entrance is double, coming together in Y shape to a narrow dirt road. About eighty feet from the entrance the road is embanked, with sharp dirt sides dropping about twenty feet to shallow pools of water.

About forty feet of the road is embanked in this fashion, and then for a quarter of a mile or so it sweeps down into a valley— all of this private road and a part of the picnic grounds. At the end of this road, there is a sheltered hollow with a broad, meadowgrass bottom, a sort of natural arena, hidden by hummocks of low hills from the sight of anyone on the public highway. It was in this hollow that the paraphernalia for the concert had been set up: a large platform, two thousand wooden folding chairs, and a number of spotlights powered by a portable generator.

-Howard Fast, “Peekskill, USA”

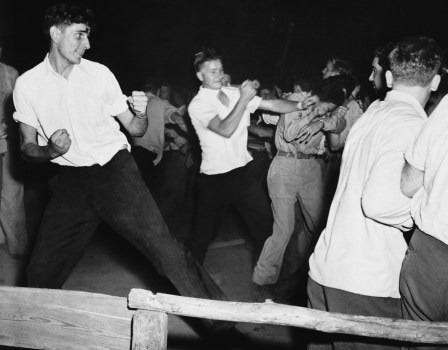

Hours before the concert, Hillside Avenue was already claimed. Dozens of cars lined the road— not concertgoers, but counterprotesters. Local veterans’ groups had rallied themselves into something they called a parade. In practice it was a rolling blockade: epithets, jeers, and men positioning cars and bodies to choke off the entrance to the picnic grounds.

When Howard Fast arrived at 6:50— about an hour before the concert— there were roughly 120 people already down in the hollow, mostly women and small children. Another car came in soon after.

It would be the last car to reach the hollow that night.

By then the “counterprotest” had curdled into a siege. At the entrance, men pressed up against the forked roads and the narrow dirt road that dropped toward the hollow, testing it the way a crowd tests a fence: leaning, surging, feeling for the moment it gives. Small knots broke off and tried to force their way down, shoved back only when concertgoers and a handful of organizers met them shoulder to shoulder in the chokepoint. But there were only thirty-so men and teenage boys in the hollow, and increasingly fewer with the strength left to fight. Above, the road was locked with cars and bodies; below, the stage and chairs sat waiting in a pocket of meadow. The trap was sprung.

Now there was a sudden brilliant glare and the hills to our left stood sharp and black against a yellow background. There was a moment of silent cessation, and one of our men leaped up on the truck and cried,

“A cross is burning!”

We could only see the glare, but the symbolic meaning was not lost upon us. In this sweet land the movement had been rounded out; the burning cross, the symbol of all that is rotten and mean and evil in our land had blessed us. Our night was complete, and we would do well to kneel before the new patriots.

-Howard Fast, “Peekskill, USA”

No one seems to know exactly when it happened— only that, at some point in the crush, a Navy veteran named William Secor suddenly doubled over with a hot, blooming pain in his side. He looked down and saw blood: a blade had cut him. The news moved faster than anything else that night. The crowd, already drunk on permission, honed into something sharper, something even more violent. It was certainly not the first blood that night, but it proved a strong alibi.

The next attack would be the most vicious.

For one thing, it was still daylight; later, when night fell, our own sense of organization helped us much more, but this was daylight and they poured down the road and into us, swinging broken fence posts, billies, bottles, and wielding knives. Their leaders had been drinking from pocket flasks and bottles right up to the moment of the attack, and now as they beat and clawed at our lines, they poured out a torrent of obscene words and slogans. They were conscious of Adolf Hitler. He was a god in their ranks and they screamed over and over,

“We’re Hitler’s boys— Hitler’s boys!”

“We’ll finish his job!”

“God bless Hitler and fuck you n⸺ bastards and Jew bastards!”

“Lynch Robeson! Give us Robeson! We’ll string that big n⸺ up! Give him to us, you bastards!”

I remember hoping and praying that Paul Robeson was nowhere near— that he was far away, not on the road, not anywhere near.

“What Medina started, we’ll finish!” they howled. “We’ll kill every commie bastard in America!” Oh, they were conscious, all right, highly conscious.

-Howard Fast, “Peekskill, USA”

Up on Hillside Avenue, the scene had tilted. Tight columns of veterans’ organizations moved through a crowd that had swollen into the thousands— townies drawn out by the weeks of agitation in the press, now standing shoulder to shoulder along the road. Traffic locked up. Engines idled. No one was going anywhere.

This said, even among the “patriotic elements,” lines were being drawn:

Witnesses testify that the Jewish War Veterans were booed, hissed and insulted even while they were participating in the anti-Robeson parade and that members of the crowd standing on the edge of the road shouted at these uniformed Jews, “Dirty K—s,” “Jew bastards,” etc.

Some of these Jewish Veterans of Foreign Wars were threatened with attack when returning to Peekskill after the parade had disbanded. This ceased when they were recognized as Peekskill men.

It has been explained to investigators that “…It’s a Commie trick to put on a uniform and say, “I fought for my country.” Those New York Jews are all Commies.”

-Violence in Peekskill — American Civil Liberties Union

The other lead organizer that night— John Zimmer, the parade’s grand marshal, climbed onto the bed of a truck and ordered the crowd to disperse. The instruction landed as a suggestion. As the parade dissolved and the concert was effectively scuttled, attention shifted: not to leaving, but to the cars— concertgoers trapped in place, suddenly visible, and suddenly vulnerable.

“The roads had been blocked in both directions. As we waited in line, a man wearing a Legionnaire’s cap came over and opened the door of our car, and said to my husband:

“Park your car over here,” pointing to the roadside, “We’re going to get these goddamned Jews.”

He walked down the line of cars, opened some car doors and repeated the same words he had used to us. Then he would skip two or three cars, and after scrutinizing the people inside, would go to the next one.”

-Violence in Peekskill — American Civil Liberties Union

Jammed in traffic was the car carrying Paul Robeson, boxed in a middle seat between two of Helen Rosen’s friends. The closer they crept, the louder it got— screams, whistles, shattering glass. Then the rocks started. The car took hits. In the confusion, they managed to peel out before anyone could positively spot him, slipping away to a friend’s cottage by Still Lake in New Castle.

But the mob wasn’t only hunting Paul Robeson the singer. It was hunting what he represented— anything that looked like spilling across boundaries, and that was exemplified in his son. Paul Jr. had recently married a white woman— widely reported on, including in the Evening Star. Another interracial couple was stopped and held while rioters inspected them, satisfied only once they accepted they hadn’t found the younger Robeson.

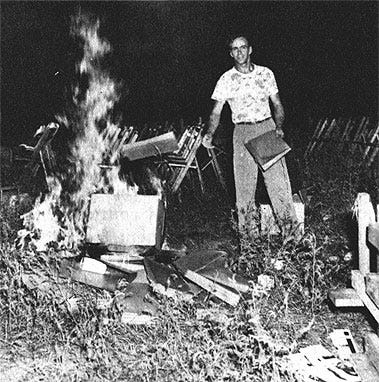

When the violence spilled into the hollow itself, it shifted from an attack to a twisted ritual. Three men climbed onto the stage and demanded the few musicians who remained perform “The Star-Spangled Banner,” a forced soundtrack for the spectacle. Others dragged wooden folding chairs into a pile, and fed them and anything else they could find into a fire.

Hours in, state troopers and Westchester County police finally arrived— peculiarly late, and not as rescuers. They began corralling the concertgoers into a clearing and detaining them on the pretext of Secor’s stabbing, sweeping the grounds for attendees still hiding in the dark. Only after word came back that Secor was not dead did they start releasing people. The rest of the night became cleanup and containment: troopers shuttling battered concertgoers home while police gathered up the “subversive materials” trawling the fields seeking evidence of a crime committed by the victims.

Three days later, a crowd assembled at Harlem’s Golden Gate Ballroom. Before the doors even opened, the overflow on Lenox Avenue turned the sidewalk into a second stump— a wider audience not subject to fire code. Benjamin Davis, Harlem’s Black Communist councilman, was out there dispatching the evening’s thesis with a line that landed as both joke and deterrent: “Let them touch a hair of Paul Robeson’s head and they’ll pay a price they never calculated.”

Davis was ensnared in the Smith Act trials— charged, in the language of the state, with conspiring to overthrow the government for the crime of party membership. Inside, he took the microphone first:

“We warn all the flunkies of Wall Street whether they wear white sheets or black robes like Judge Medina, that we are peace-loving people. But we are not pacifists and we’re going to stand up toe to toe and slug it out.”

”We are going to protect ourselves!”

”They talk about us overthrowing the government, but they don’t say anything about the government overthrowing the people.”

When the ballroom hit capacity, Robeson finally spoke— braiding his remarks with song:

“I’m going back to Peekskill with my friends and they’ll know where to find me.”

”This marks the turning point. From now we take the offensive, and that offensive begins tonight at this meeting.”

”The surest way to get protection is to show them from now on we’re going to protect ourselves!”

He closed by singing “No More Auction Block:”

No more pint of salt for me

No more peck of corn for me

No driver’s lash for meNo more, no more!

In four days, he would sing in Cortlandt.

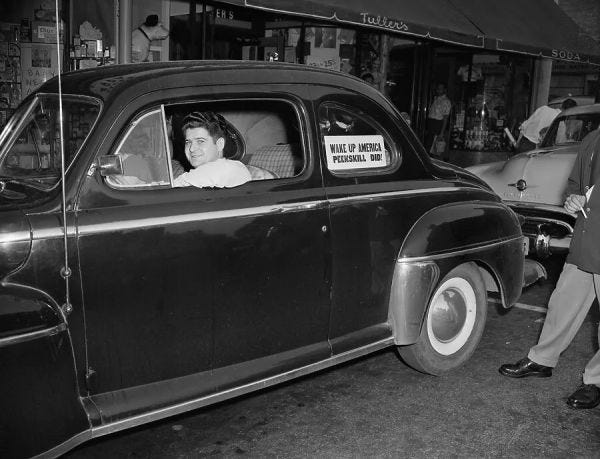

Harlem answered with song; Westchester answered with gunfire. In the dead of night, shots were fired at the home of the owner of the Hollow Brook Country Club— slated to host the next concert. Bumper stickers, lawn signs, banners began being printed:

“WAKE UP AMERICA, PEEKSKILL DID!”

Eugene Bullard’s name should be everywhere.

Born in Columbus, Georgia in 1895 to a former slave— seventh of ten children— he learned early that his world planned to suffocate him. He would later recall being “as trusting as a chickadee and as friendly,” sheltered, briefly, by the small mercies of youth— believing people were basically decent— right up until the one-two punch that snapped the illusion. At age seven, his mother died. At eight, after his father fought with a racist supervisor, a lynch mob came. His father survived— lights off, shotgun pointed at the door— but that’s an experience you can’t shake: the knowledge that your neighborhood can become a noose with a few hours’ notice.

Bullard’s response wasn’t acceptance. It wasn’t patience. It was escape.

He ran away as a boy— accounts vary on his age, eleven maybe, which is itself telling: when you’re a Black kid in the Jim Crow South, your biography doesn’t get kept with particular care. He fell in with the Stanley clan: English Romani horse-racers roaming rural Georgia and absorbed a dangerous idea: that someplace else might treat him like a person.

At sixteen, he did what the United States has always found unforgivable in the people it mistreats: he left. He stowed away on a German steamer out of Norfolk, landed in Scotland, and described it like crossing a membrane— being “born into a new world.” He drifted through England on whatever work would have him, even serving as a carnival target; humiliation paid better than starvation.

Then he reached Paris— the city that, in ten thousand American stories, makes artists and frees women and reinvigorates everyone who touches it. In Bullard’s case, it did something more basic: it gave him space to breathe. He learns French, lived by his wits, and threw himself into boxe anglaise.

He boxed. That mattered— not just because it put money in his pocket, but because it was one of the few professions where a Black man could be publicly exceptional and have a crowd pay to watch it.

Then Europe detonated.

At nineteen, he enlisted in the French Foreign Legion. He fought at Verdun, was torn up by shrapnel, and earned the croix de guerre— an honor that said, unambiguously: you belong here. He changed his middle name from James to Jacques.

But he wasn’t done yet.

His injuries kept him from returning to the infantry. In recovery he met a pilot, wrangled his way into aviation, and got his license seven months later: the first Black American pilot, no additional qualifiers. When the United States entered the war, he applied to fly for the American Expeditionary Forces and never heard back. He crossed an ocean to escape Jim Crow, and it still found him.

After the war, Bullard stayed in Paris and built yet another life: nightclub impresario, gym owner, fixture of the Black expat scene— Josephine Baker babysitting his kids, a young Langston Hughes washing dishes. When war returned, he volunteered again, first in counterintelligence, later in the defense of Orléans. A German shell threw him into a wall; he hitchhiked to Spain with a damaged spine that would haunt him for life.

And then he came back— to the country of his birth, after twenty-eight years.

His fourteen medals and Paris notoriety did not follow him to Harlem. He took odd jobs: security guard, perfume salesman, interpreter for Louis Armstrong. The story doesn’t resolve into triumph; it resolves into America being America.

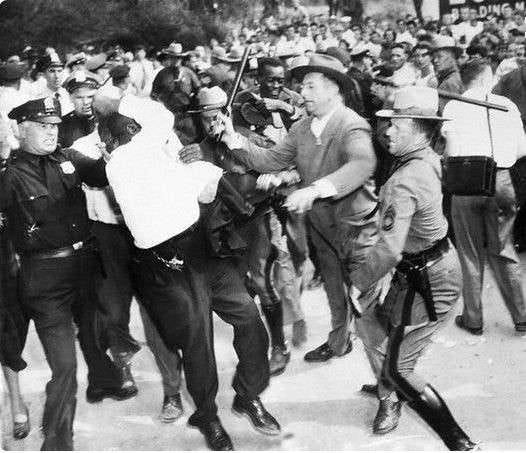

And at fifty-one, he was photographed being beaten by state troopers— for the crime of letting a friend talk him into going to a concert upstate.

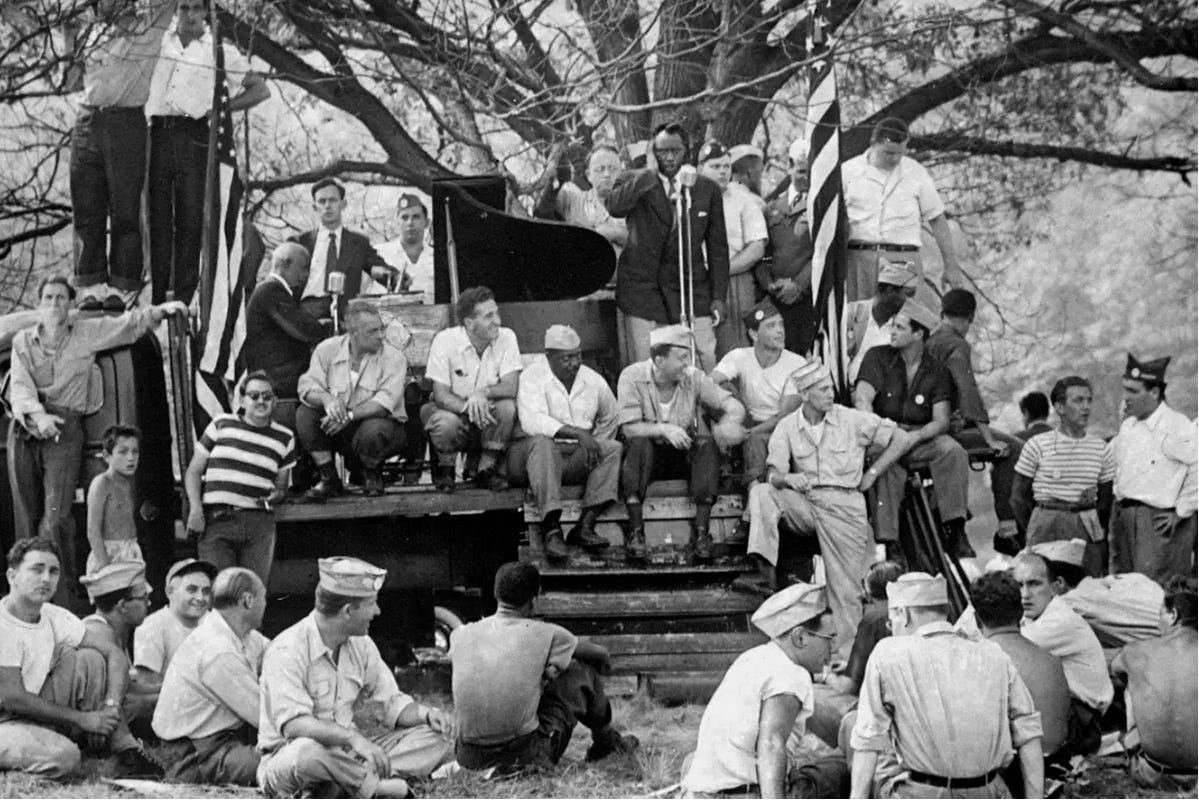

The second concert didn’t simply change venues. It changed time. The first was an 8 p.m. affair— the kind of darkness that helps a mob pretend it’s anonymous. The second was set for 2 p.m., broad daylight. Press would be there. The authorities would be there. If the first riot could be filed away as whiskey-fueled hooliganism, the second would be harder to launder. That was the point.

And in the hollow, for a couple of hours, it worked.

Robeson arrived under escort. Men fanned out into a loose human ring around the seats. American flags bracketed the stage; veteran’s caps dotted the crowd like punctuation. Around 20,000 people turned out. “The Star-Spangled Banner” opened the program— this time by choice, not by coercion— followed by pianists moving through Bach and Chopin, then-obscure Pete Seeger, and then Robeson fulfilling the promise he made in Harlem.

The daylight seemed to be doing its job. From a vantage point in the hollow, for a few hours, the state managed to perform what it always claims it can do: keep order.

Outside, the violence had already started.

As cars and buses began to thread back out, they had three options—north or south along Hillside Avenue, or east on Red Mill Road— and all three were waiting. Not chaos, not chance: hunting grounds. Sentries with hours of preparation.

A few reporters clocked it in advance— because it wasn’t subtle. One New York Times reporter watched men stacking stones into cairns along the roads as if they were marking a trail. Others saw cars already loaded with basketfuls of rocks. A pickup truck shuttled hecklers from the center of Peekskill out towards the bottlenecks.

And then: state troopers directing traffic.

This is the hinge. A dizzying number of troopers were present that day; they weren’t absent— and the moment they started “managing” the exit, the story stopped being “locals got out of hand” and becomes what it actually was: the state guiding a column of civilians into an ambush it had every reason to anticipate. Call it incompetence if you need the comfort of a neutral word. Call it the primal reflex of looking the other way when the right people are doing the hurting. But from behind the glass it feels like what it is: a trap.

And it didn’t just happen to the hotheads and organizers. Every single person there— drivers, passengers, women, men, kids— had to run that gauntlet. It was indiscriminate.

I tried to walk it. After four miles, snow and a narrow shoulder proved it impossible to reach the kill zones.

So I ducked into a strip mall pizzeria for two slices and enough water bottles to hit the $10 card minimum. A fireplace looped silently on a flatscreen. A guy comes in to riff with the staff— “…es Trump, vamos a tomar Groenlandia, a tomar Colombia, a tomar Dinamarca, dios bendiga a los Estados Unidos…” And then it was an Uber, the station platform, a train closing in from the mountainside: the clean, efficient choreography of getting back.

For the people in the cars, there was no choreography— only endurance:

The rocks began again, and I jockeyed on. We had gone over a mile now. The car ahead pulled over to the side and the driver sat with his head hanging over the wheel. His head was bloody all over.

After a mile and a half there were no more large, organized groups of rock-throwers, but individuals instead. An occasional crashing blow reminded us of the individuals. (But further on, three, four, five and ten miles from Peekskill, organized groups were stationed on every overpass, to pelt the cars below with rocks. In this way, many cars which had never been near the concert that day were badly smashed and their occupants hurt.)

-Howard Fast, “Peekskill, USA”

Hourlong drives felt endless until they turned onto familiar streets. By the time the dust settled, more than 140 people had been injured— windshields cratered, windows blown out, bodies cut and bloodied— an entire crowd made to pay for the crime of showing up in daylight.

As one group reached their destination— they discovered that someone had slapped a sticker onto their bus:

“COMMUNISM IS TREASON. BEHIND COMMUNISM STANDS— THE JEW! THEREFORE, FOR MY COUNTRY— AGAINST THE JEWS”

-Violence in Peekskill — American Civil Liberties Union

An interesting document is found in Robeson’s FBI file called an “Inquiry on Racial Incitations Practiced by Communists.” The author, unnamed, was paid $1,200 by the State of New York to create it for the Westchester Grand Jury. The official memorandum adding it to the file notes that it was also “being made available to American Legion Posts in the United States through the National Americanism Commission and [REDACTED] felt that such information should also be made available to the Bureau.”

“It must be stated to the credit of the American citizens of negro extraction, that all major negro organizations in the United States as well as the negro press, with few exceptions, have repudiated Robeson’s Paris declaration of disloyalty and that less than a fifth of the total numbers of demonstrators were negroes.”

“…the following appear to be the motive for this C.P. [Communist Party] organized demonstrations”

“1. To start a fresh build-up of Paul Robeson as a representative of the Negro Race…”

“2. To take the offensive especially amongst the negroes, for a campaign of disloyalty to the U.S. in case of war with Russia.”

“3. A hostile semi-rural neighborhood within easy reach of New York was deliberately selected with a view of dramatizing alleged disloyalty of the negroes as expressed in the person of Paul Robeson clashing with the loyal white populace of the county.”

“4. The C.P. real organizer of this meeting, fully anticipated the antagonism of the patriotic elements of the county. They sought under the cover of free speech protection from the County authorities for their August 27 disloyal demonstration.”

“5. Having failed to obtain that protection at the first meeting, the C.P. mobilized all communist-controlled organizations in and around New York for the second turnout of September 4, to force the issue of unlimited free speech and to further emphasize the hostility between the loyal whites and Robeson’s disloyal negroes.”

“6. The C.P. strong arm, the socalled [sic] “Security Guard”, was mobilized to intimidate, beat down and disperse the loyal whites in case the authorities failed to furnish protection for the demonstration.”

“7. The hostility of the police authorities protecting the meeting towards the “Security Guard” may have been anticipated by the C.P. high command, but they were willing to risk the mass display of the “Guard” to show its strength as well as to test the “Guard” itself under actual battle conditions.”

“The reason why the C.P. selects a theatrical extrovert type like Paul Robeson to lead off its negro incitation program will be better understood when the program is fully explained. In short a theatrical program requires a theatrical personality.”

“THE JEWS:”

“Second, in importance, in the racial incitation politics of the Communist Party, are the Jews.”

“…because the Jews, more experienced in things of ideology and politics [than Black people], are beginning to see through the trickery of the Communist High Command in Moscow.”

“The Communist have played around with Jewish nationalism off and on also, but their main stalking “horse” amongst the Jews has been the issue of Anti-Semitism which they have exploited to the ‘nth degree.”

“If one were to estimate the racial or national background of the Communist demonstrators at Peekskill in the order of their numerical importance, the following approximately would be the result:

1. Jews: 8,000

2. Slavic Groups: 3,000

3. Negroes: 2,000

4. Latins & Italians: 1,000

5. Anglo-Saxons: 1,000”

On the floor of the House, Jacob Javits rises to speak. A liberal Republican from the Jewish tenements of the Lower East Side— raised helping his mother sell nonperishable goods from a pushcart to morning commuters, a kind of backstory New York loves to romanticize only once it’s safely in the past, not on the 6 train— to night school at Columbia and now the halls of Congress, Javits has learned to speak with tact, even under duress.

He declares plainly that the Constitution must apply equally in North and South. The law, he says, should fall “with equal weight on the hoodlums who participated in the riot as well as on any Communist or Communist sympathizers who incited it.” He connects the blood on Hillside Avenue to the long-fought battle for federal anti-lynching legislation. But it is not enough.

Then comes John Rankin.

Rankin. A progressive Democrat. A New Dealer. Co-author of the Tennessee Valley Authority Act. Chair of the House Committee on Veterans’ Affairs. And a man whose name should long ago have been buried under a thousand censures and a hundred expulsions.

This is the same Rankin who once glared at a House gallery full of Black Washingtonians, shouting that an anti-lynching bill was “a bill to encourage Negroes to think they can rape our white women!”

He now takes the floor to respond:

“Mr. Speaker, it was not surprising to hear the gentleman from New York defend that Communist conclave in New York where Paul Robeson, the negro Communist, sang the praises of Moscow and criticized the patriotic ex-servicemen who protested.

The American people were not in sympathy with that gang of Communists who composed that traitorous gathering. When they now undertake to investigate and persecute those ex-servicemen who made that protest, those brave patriots who wore the uniform, who suffered and bled, and who saw their buddies die in two World Wars, when they begin to investigate them for trying to break up that Communist meeting, the American people are with the ex-servicemen and not with that n⸺ Communist and that bunch of Reds who went up there from New York to put on that demonstration.”

Vito Marcantonio, the only American Labor Party member in Congress, the other warm-up act to Robeson at the Golden Gate Ballroom, another icon of Uptown’s socialist past, renders an objection to the slur and demands it be stricken from the record.

Speaker Sam Rayburn of Texas mutters that Rankin had said “Negro.” Rankin, eager to earn his moment, screams over him:

“I said niggra, just as I have said ever since I have been able to talk, and shall continue to say.”

Rayburn shrugs it off and rules from the chair: Rankin had “referred to the Negro race, and they should not be ashamed of that designation.”

The Congressional Record will read “Negro.”

Seventy-six years later, the proceduralism is still with us— the same clerical magic. It didn’t die with Rayburn; it just learned new euphemisms and picked new targets, keeping the confidence trick: the chair’s gentle amnesia. I’m not up-to-date, the chair says, like it’s a neutral fact, like it absolves him. I’ll look into it, as though the problem was terminology and not open contempt.

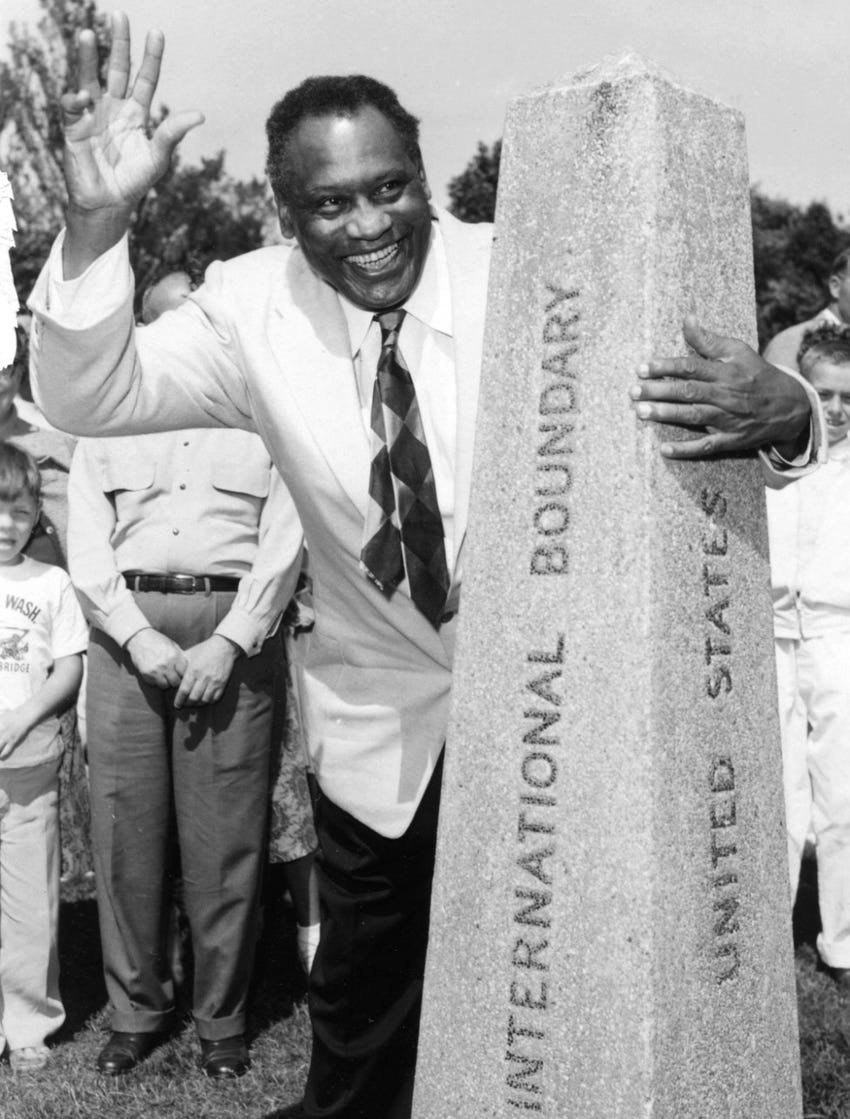

Robeson left Peekskill alive. That is the only mercy this story offers him.

The mob didn’t finish the job on Hillside Avenue, but it didn’t have to. After Peekskill, the punishment for what he did not say in Paris— and for what he had said and done everywhere else— was far more orderly. He got the kind of slow professional suffocation that leaves enough plausible deniability.

His passport was voided in 1950, and his blacklisting from venues and international touring dropped his income from $150,000 a year to $3,000. His only shows to a foreign audience over next eight years were at the Peace Arch Park— an international park straddling the border of Washington State and British Columbia. He sang from a flatbed truck on the Washington side.

He continued to be outspoken, and not always prudently. He offered explicit, personal praise of Josef Stalin. He was awarded the Stalin Peace Prize in 1952, and penned his eulogy after Stalin’s death. After Khrushchev’s “Secret Speech,” he shut the door on the subject— declining to comment on Stalin for the rest of his life.

Hauled in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1956 after he refused to sign a sworn affidavit denying he was a Communist, he invoked the Fifth and was grilled on a variety of other topics:

Paul Robeson:

“In Russia I felt for the first time like a full human being. No color prejudice like in Mississippi, no color prejudice like in Washington. It was the first time I felt like a human being. Where I did not feel the pressure of color as I feel in this Committee today.”

Congressman Gordon Scherer:

“Why do you not stay in Russia?”

Paul Robeson:

“Because my father was a slave, and my people died to build this country, and I am going to stay here, and have a part of it just like you. And no Fascist-minded people will drive me from it. Is that clear? I am for peace with the Soviet Union, and I am for peace with China, and I am not for peace or friendship with the Fascist Franco, and I am not for peace with Fascist Nazi Germans. I am for peace with decent people.”

Congressman Gordon Scherer:

“You are here because you are promoting the Communist cause.”

Paul Robeson:

“I am here because I am opposing the neo-Fascist cause which I see arising in these committees. You are like the Alien Sedition Act, and Jefferson could be sitting here, and Frederick Douglass could be sitting here, and Eugene Debs could be here.”

Chairman Francis Walter:

“Now, what prejudice are you talking about? You were graduated from Rutgers and you were graduated from the University of Pennsylvania. [sic] I remember seeing you play football at Lehigh.”

Paul Robeson:

“Just a moment. This is something that I challenge very deeply, and very sincerely: that the success of a few Negroes, including myself or Jackie Robinson can make up— and here is a study from Columbia University— for $700 a year for thousands of Negro families in the South. My father was a slave, and I have cousins who are sharecroppers, and I do not see my success in terms of myself. That is the reason my own success has not meant what it should mean: I have sacrificed literally hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of dollars for what I believe in.”

His passport was returned in 1958 after Kent v. Dulles, a 5-4 Supreme Court decision. He toured again. He attempted suicide in a Moscow hotel room in 1961. He was in and out of treatment in the Soviet Union and later East Germany— including electroconvulsive therapy and heavy medication— until he returned to the United States two years later, where he lived in seclusion. He died in 1976.

Ol’ man river

That ol’ man river

He mus’ know somethin’

But don’t say nothin’

He jus’ keep rollin’

He keeps on rollin’ alongHe don’ plant taters

He don’t plant cotton

Them that plants ‘em

Is soon forgotten

But ol’ man river

He jus’ keeps rollin’ along!

-Robeson as Joe in the musical Show Boat (1927) (spelling normalized)

There are many historical markers along Oregon Road, none about the events of that day. The town’s Master Plan Committee does register a note in the Historic Place of Importance list— “Paul Robeson Concert in 1949, Oregon Road” sits between a stone pump house and a 1700s homestead. The golf club that was built on the site of Lakeland Acres mentions the riot and the 50 year commemoration of it on their website— good! Maybe a few good teachers mention it in passing. But if you drive Oregon Road with no prior knowledge, nothing tells you what happened here. The landscape doesn’t.

In some ways, what happened after Peekskill is harder to repeat. There are those bold enough to be quoted, those whose faces are recognized by aging locals in old photographs, but for the vast majority of participants, history has already lost them in the crowd.

In comparison, each of our lives will be gratuitously overdocumented. Even the average person leaves a thick trail that future historians must wade through: every post, every quip on current events, every high-resolution video shot on devices carried in every pocket. The record will not be perfect, but it will be dense.

The best the powers that be can do is tell us to deny what we see with our own lying eyes. That works sometimes— but temporarily. For all the horrors committed today (and there are many), there may not always be a path to legal justice. Headlines move on frustratingly fast and without resolution. But for those who come after us, there will be a record— and names attached from the petty functionary to the highest levers of power.

Time doesn’t make people honest, but it does often blunt the reflex to defend your “side” at all costs. A point is reached where we stop imagining we’d have been them; their actions become alien to both sides of the current fight. New people move in and inherit the community without inheriting the shame, and the oldest alibi in the book— “products of their time”— becomes the town’s way of keeping the past at arm’s length.

Peekskill sits squarely in a horrifying middle zone: so many detailed accounts of what happened, and so few named perpetrators. Most of them went home, slept fine, maybe felt some slight unease decades later about that particular unpleasantness and died peacefully at Hudson Valley Hospital or retirement homes in Florida surrounded by loved ones who scrambled to be by their bedside. There was at best private remorse, hardly a reckoning.

Do we still get to die without one?

Editor’s note: This piece draws on contemporaneous reporting— especially from the Associated Press, New York Times, and the now defunct (and in this piece, pilloried) Peekskill Evening Star. Collections from the New York Public Library and Peekskill’s Field Library were invaluable, supplemented by research and photography trips— to Peekskill and Cortlandt for the riot’s physical geography, to Harlem for the community response, and to Princeton, Somerville, and Philadelphia to trace the life of Paul Robeson. The recent docuseries “The Peekskill Riots” by filmmaker Jon Scott Bennett also deserves due credit for source recovery and contributing to the broader historical context and narrative understanding that informs this piece. I encourage readers to watch it for a more in-depth account than I can provide here.

Scripture quotations are taken from the New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition. Copyright © 2021 National Council of Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

I am additionally indebted to my step-grandfather Marc Wiesenberg— who grew up in Peekskill’s small Jewish community in the period in question— for his childhood memories of the atmosphere surrounding the Peekskill riots. His recollections informed the texture of this piece.

The Hudson Line will be on hiatus while I focus on other work. Whether this is the first piece of mine you have read or you’ve been here for all two and a half years, thank you for reading.