Molinaro's Gambit

Growing pains of Tivoli's kid mayor

NOTE: This is the free version of yesterday’s article, which as always was pre-released early for paid subscribers.

I can’t tell you when exactly I met Marc Molinaro. My best guess would be either when the Walkway over the Hudson opened when I was 6 or the annual Dutchess County Fair around the same time. I couldn’t tell you if I knew he was a politician or just an unusually gregarious man, but what I do know is I cannot remember a time when I was not at least vaguely aware of him. I’d wager this is the case for most who like me grew up in Dutchess County in the 2010s.

Everywhere in the country has politicians who engross themselves in that hyperlocal circuit, but Molinaro was a whole different beast. Every time there was a spare block of time and a new shop opened, a class graduated, or a stretch of rail trail was opening, he was there. When he couldn’t be, he found alternatives. The thumbnail for this article is a letter I and every other Dutchess County senior graduating from high school in 2021 got, a Comic Sans kudos to us for making it through COVID and beginning our adult lives. Not photocopied or auto-penned, hand signed.

Molinaro won his first election at age 18, became mayor of his hometown at 19, defrocked a decade-long incumbent assemblyman at 30, and was county executive at 36. In that last role, he routinely overperformed Democrats by double digits. In 2018, Democratic Senator Kirsten Gillibrand won Dutchess County by 14.8%. As an at the time popular Andrew Cuomo cruised to victory on the same ballot against Molinaro’s doomed, underfunded gubernatorial run, Molinaro won Dutchess by 7.0%. While Molinaro lost to Cuomo by 24 points statewide, he actually overperformed Lee Zeldin’s 2022 gubernatorial run in 23 upstate counties, including being the last Republican to win now solidly blue Schenectady and Columbia counties.

Molinaro today is a first-term backbencher in the GOP’s razor-thin House majority. He lost his first competitive race ever in a special election for Congress, only winning the district’s portion of Dutchess which excluded the most blue cities of Poughkeepsie and Beacon by a mere 3 points. He won the general election by an even slimmer 1.56% in the most favorable electoral environment for the New York GOP since the 1990s. His new district contains none of Dutchess County, where he cut his teeth as a politician for over half his life, including numerous electoral overperformances deep into the Trump era. The congressman who proudly stated he did not vote for Trump only 6 years prior has endorsed him this cycle, and with less than two months to go rapidly careens towards what looks more likely by the day: at age 48, Marc Molinaro may soon be out of office for the first time since he was a teenager.

All this begs the question: what happened?

— 19-year-old Marc Molinaro, shortly after his election as mayor of Tivoli

Molinaro’s story, like that of many in the Mid-Hudson (though most will not admit it), begins much further downstate. Born in Yonkers in 1975, his parent’s divorce and single mother’s financial hardship found him in a far rougher Beacon than exists today and even further up the river in 1989.

Tivoli, population 1,035 in 1990 and 23 people smaller now, is a prototypically Hudson Valley village. Nestled in the northwest of Dutchess County between Route 9G and the Hudson River, Tivoli isn’t a one traffic light town— it’s a zero traffic light town, unless one is semantic enough to count the blinking yellow lights at the corner of 9G and Broadway installed just a few years ago. It is postage stamp sized at 1.55mi², most residents live along either Broadway or Montgomery Street unless they live in a small development behind Tivoli Park.

An older Victorian brick building sits along Broadway. A historic marker coins it the “Watts De Peyster Fireman's Hall.” It has always held dual purposes, initially it doubled as a firehouse and the village government’s offices, but with a new firehouse being built in 1986 the other half is now the village library. These village offices are where Molinaro found himself between his election to the Board of Trustees at age 18 and his resignation as mayor to become an Assemblyman at age 32.

There is I think something of a horseshoe shaped curve to the difficulty of being an elected official. One end is obvious, where decisions of great global consequence rest on the shoulders of just a few powerful people. At the other end, it is much less obvious, and I think few offices exemplify it as well as mayor of a small town. Every local gripe from noise complaints to bear sightings to boundary disputes isn’t just listened to and resolved by some underling, but you yourself. To be a leader in a community so small is to nearly guarantee you will be personally known to them. If said gripe is not solved, you are individually to blame and word of your failing spreads quick. It is an environment dominated by individual personalities.

This is of course nothing new. John Watts de Peyster, as in “Watts De Peyster Fireman's Hall,” was like the namesakes of most buildings of that era a wealthy New Yorker with a summer home nearby. He was elected village president and did the community a service by bankrolling its construction… and then approving the contract to lease the building for the village from himself. At various points he evicted the village government from those quarters at his own whim, such as when they raised taxes in 1900. A few years later, when his estranged son was elected village president, the village was only permitted to use the space if he was barred entry. Money is as effective a carrot as it is a stick.

There is a reason village government in the Hudson Valley has such high turnover: it is a very interpersonally demanding job. The decisions you make reverberate through the community in ways that invariably will make some section of the population despise you. In communities as small as Tivoli, your ability to hang on despite that will be dependent on your ability to greet hundreds by name at community events, shake hands, plant trees, run towards every fire alarm, and otherwise execute perfect retail politics lest the scion of some other hyperlocal family challenge you. Few are cut out for this role. But few 19-year-olds are elected the youngest mayor in America. Between community college classes (Molinaro, whose first victory scuttled his attendance of SUNY Cortland, is one of five congresspeople whose highest educational attainment is an associate’s degree) and village board meetings, Molinaro found his way.

Molinaro engrossed himself in this role, a formative period very indicative of his later philosophy in campaigning. His eyes however, clearly laid beyond. In 1999, he sought and won a seat in the Dutchess County Legislature, giving him the additional monthly drive to Poughkeepsie on top of his responsibilities as mayor. His constituency expanded to the rest of the town of Red Hook (which Tivoli is part of) as well as Milan and Clinton. However, two simultaneous elected offices would fail to satisfy him.

“I was ready to retire, but I didn’t realize it.”

- Patrick Manning, NYS Assemblyman (R-103rd, 1994-2006)

Molinaro was 30 years old and in his sixth term as mayor when an opportunity for further advancement beyond the Gilded Age building on Broadway presented itself. Facing polling armageddon against popular Attorney General Eliot Spitzer, third term Republican governor George Pataki opted against seeking re-election in 2006. This kicked off a mad scramble for the opportunity to succeed him. Amongst the candidates were current Secretary of State Randy Daniels, Assemblyman and future Congressman John Faso, the former governor of Massachusetts Bill Weld, and of greatest relevance to us Assemblyman Pat Manning.

Manning’s career has a surprisingly similar streak to Molinaro’s. Elected to the Dutchess County Legislature at age 26, he became the youngest assemblyman in New York history in 1994. And like Molinaro, his eyes clearly always looked towards higher office. The seat he would be vacating spread from East Fishkill, the farthest ring of pre-Recession exurban NYC development, to the town of Canaan in the northeastern corner of Columbia County, a quicker drive to Boston than New York City. Also included of course was Molinaro’s own Tivoli, and so Molinaro quickly cleared the field.

There was a problem though. Only a few months before the primary that would coronate Molinaro, Manning’s gubernatorial campaign was floundering. Failing to coalesce support amongst conservatives and rocked by allegations of an extramarital affair, Manning dropped out of the race and announced he would seek re-election to the Assembly. Molinaro decided to stay in, overnight transformed from shoo-in to challenger.

I have thought a fair bit about how to present this election, as while I have been aware of it for many years, it has gone practically unmentioned since Molinaro’s rise to Congress. This is a race far more primed for the medium of a Jon Bois video than a Substack. So in the spirit of an experience I had lately and will soon write about, let’s look under the hood.

These are the town-by-town results of the 2006 NY-103rd Republican primary, sorted by population and with one town’s figures conspicuously missing. It should be rather self-explanatory, but one thing that may not be is the eligible voter and turnout numbers. The Dutchess County Board of Elections was kind enough to provide me with their party registration figures from 2006, so we can get accurate numbers for what share of eligible voters (registered Republicans) actually voted. Columbia County meanwhile does not have this data readily available, and so their towns have no data for those fields.

Molinaro has done quite good for a challenger, but with only one town outstanding is still down to the incumbent Manning by 289 votes, about 6.20%. Manning has really run up the score in his hometown of East Fishkill, one of the aforementioned McMansion filled towns in the outermost exurban ring of New York City. He netted 283 votes there, just shy of his entire lead. Molinaro has done quite impressively near his home turf, the town of Milan in his legislative district and neighboring Pine Plains just outside of it (the town of Clinton while in his county legislative district was not in this state assembly district). They are amongst the smallest towns in the district though, and so those decisive wins only net Molinaro 92 votes.

As I’ve said though, I have left a town out. Red Hook, which contains the village of Tivoli, is a larger town relative to most in the district but still has just over a third the number of registered Republicans as Pat Manning’s hometown. Still, it can be expected to go favorably for him and turnout might even be spiked by the presence of a known face. As a hypothetical, let’s crunch some numbers where turnout is about 5% higher than in the highest turnout town, and where Molinaro does 5% better than in his best town, his 72% with the 74-person electorate of Milan.

In this scenario where Red Hook has the highest turnout in the district by far and Molinaro holds Manning to an almost inconceivably low for a long time incumbent 23%, Manning would still eeke it out by 5 votes. With that said, these are not the actual results of the primary, and I suspect you understand where I am going with this:

Marc Molinaro, age 30, got 89.85% of the vote in Red Hook against an incumbent assemblyman who had been in office since he was in high school. Turnout among registered Republicans in Red Hook was 1.7 times higher than the next highest town, cracking 30% in a sleepy Bush midterm primary where the only other race on the ballot was to determine who got to lose to Hillary Clinton by 36 points in November. With 584 votes to Manning’s 66, Molinaro netted 518 votes in Red Hook to win by a margin of 229 votes. Who ever said retail politics was dead?

“It’s a thought. It’s something that I’ve been asked to consider and I’m considering it.”

- Marc Molinaro, prospective 2010 candidate for Congress

Molinaro at this point encountered something he up to this point had not: his ceiling. He was a Republican in New York. While his first foray into politics was as a high school intern to Democratic Assemblywoman Eileen Hickey and he initially registered in increasingly blue Tivoli as a Democrat, by his tenure in the county legislature his colors were firm. Molinaro was a rank-and-file member of the eternal minority party in the Assembly.

The Democratic Party has held a majority in that body since the 1974 elections, though the State Senate had a Republican majority that was increasingly shaky. Molinaro continued to overperform in general elections, re-elected in 2008 by 23 points in a district Obama carried by 4, but the lack of opportunity for further advancement was palpable. But where could he go?

Tivoli’s State Senate seat was reliably Republican, last held by a Democrat for less than two terms in the 1910s, (he went on to do other things) but incumbent Stephen Saland showed no sign of retiring anytime soon. Tivoli’s Congressional district, a ten-county sideways-T stretching from central Dutchess through the Capital Region into the Adirondacks, was quite swingy, but Blue Dog incumbent Kirsten Gillibrand was also a habitual overperformer.

When she was appointed to succeed Hillary Clinton in the Senate, her successor Scott Murphy narrowly won the 2009 special election to replace her, narrowly enough for Molinaro to openly flirt with a run in 2010, a run he did not end up making. That year’s Republican nominee Scott Gibson would go on to defeat Murphy by 10 points.

Why did Molinaro pass up the opportunity? His publicly stated reasons at the time were simple enough, that he was raising a young family and that he was “very happy focused on my work in the Assembly.” One of these I believe far more than the other.

The unspoken elephant in the room however is one Molinaro is intimately familiar with: money. Raised in poverty, Molinaro often tells a story of how a county food stamp administrator was rude to his single mother over the mere state of needing welfare. I have heard it many times in debates, at events, in interviews, and I don’t believe he has ever gotten more specific than that. “She must have had a bad day and made my mother feel small, and made her feel so worthless,” he said in one such interview with the Times. “I saw at that moment what a person with a degree of power could have.”

What teenager would have the audacity to seek to lead their community? Off-the-charts self-righteousness and ego are the most obvious, and the scale model of the White House in the Tivoli mayor’s office hardly absolve him of this. But by the time he had that office in the old firehouse, he was used to putting out fires. The cable and electric bill, the foreclosure notices, the repossession of his mother’s car, and the cold tightening fist of the Clinton-Gingrich safety net which saw families like his, unemployed mothers like his, as freeloaders. Those raised under the gun of poverty grow up quickly, a buoy forced by the tides of public policy that may as well hurry up and try to have a scrap of that power for themselves, to wield it for some good. It does not cost a dime to knock on your neighbor’s door.

While competitive at other levels of government, a safe Republican Assembly seat does not make for great fundraising. Where money does exist in Dutchess and Columbia counties, it is not in the hands of the historically Republican townies, but those of the New York City intelligentsia, the liberal, less affable than they believe weekenders and country home owners who do things like run Gore Vidal or Sean Eldridge for Congress from the stoops of their mansions without a lick of self awareness over half a century apart. Money is with the well-born, the Roosevelts, Watts de Peysters, and in the rare case a family of means hold less-than-liberal politics, chances are high it is their progeny seeking office. On the southern fringe of the 20th Congressional, raising his 8-month and 5-year-old children between long commutes to Albany, Molinaro could not make up for this lack of money with his time.

Molinaro won his biggest victory yet on that year’s ballot, steadily upping his margin from 11 points in 2006, 22 in 2008, and 33 in 2010. Redistricting next cycle however presented great uncertainty. The unspoken bargain in Albany was that the State Senate would be gerrymandered to maintain the Republican majority, and the Assembly the same for the Democrats. Molinaro’s 103rd was very obviously on the chopping block, with one clear way to neutralize it being to transfer Molinaro’s own Red Hook to Kevin Cahill’s safe blue district and have the Dutchess-Columbia district take in the Town of Poughkeepsie. This would be exactly what ended up happening, though Molinaro would avoid it. In early 2011, longtime Dutchess County Executive Bill Steinhaus announced his retirement.

- Michael Cunningham, employee laid off by IBM

March 30th, 1993 is a day just over ten years before I was born that may as well be tattooed on every child of the Mid-Hudson’s palm. On that day, 60,000 employees of IBM, thousands of which were manufacturing and administrative workers in their factories in Poughkeepsie, Kingston, and East Fishkill, were designated “surplus.” The company that had kept their entire payroll through the Great Depression, the company that all four of my grandparents and three generations of my family were employed by, the company whose presence not only kept this area afloat through the rust belt decline of manufacturing and agriculture, but spurred the development of entire towns and ensured upward mobility for decades, was now laying off over 55% of their staff in the region. From peak employment in the 1980s, IBM’s staff in the Mid-Hudson is now 89.7% smaller.

While few families had prepared for this day, IBM certainly did. Private security stood watch outside each manager’s office, police cars idled in the parking lots, town officials even requested that nearby gun stores to shutter for the day. IBM, long placated by every incentive and tax subsidy they ever asked county government for, had finally cut off their right hand and condemned us to damnation. IBM held a near monopoly over the rapidly expanding computer business and lost that same monopoly at a pace only matched by companies met with successful antitrust action. In the communities that bent over backwards to accommodate them, IBM would no longer be holding up their end of the bargain.

This article may not be about IBM, but no full accounting of Mid-Hudson Valley politics from the Second World War to today is complete without some mention of the economic armageddon this brought. One cannot grow up walking by those abandoned factories and the boarded up shops, churches, and hospitals hit by the aftershock and ever hear “surplus” as a neutral word. One learns at a very early age in the Mid-Hudson that they exist in the after times, occupy a world sapped of economic mobility, filled with monuments and relics of when opportunity was plentiful. And on that day when the hand that fed us for 40 years disappeared, at the helm of county government was Bill Steinhaus.

Steinhaus, like many of us, was raised by IBM employees (“IBMers,” as connected families refer to themselves) in a town IBM built, exurban Wappinger, taking the warm corporate paternalism that defined generations as a simple given. Steinhaus also started in politics young, winning the 1978 Dutchess County Clerk race at age 28. By his 1991 run for executive, the writing was on the wall that the economy would soon be forced to diversify. He would not even finish his first term in office without finding himself holding the bag.

Dutchess County was suddenly on the verge of insolvency. Property values were falling off a cliff, sales tax fell by $6.5 million, and under threat of even more layoffs, the Town of Poughkeepsie lowered the tax assessment of IBM’s Poughkeepsie campus by $93 million. The Kingston and East Fishkill plants were soliciting reductions to a similar magnitude, eventually shuttering entirely. Steinhaus responded by raising property taxes dramatically and laying off over 20% of county employees, closing entire county agencies. The fifth Republican of six county executives in the reliably red county, the third prong of his strategy was to turn again to the private sector, providing steep tax cuts to corporations and developers to redevelop some former IBM sites and attempt to create some portion of work for the newly unemployed, a plan met with muddied results but an occasional success. The election of another fiscal conservative George Pataki to the governor’s office in 1994 was another boon to Steinhaus, implementing “business-friendly” tax policy at a level outside his control.

Under Steinhaus’ 20-year tenure as executive, what were thought to be the end times ended up ever so slightly better than expectations, and the county Republicans reaped the credit. Even property values came to rebound as the southern portion of the county was re-developed into gaudy NYC exurbs, until the money faucet turned off with the Great Recession. There was also in this period another critical pivot, by some miracle (and a lot of public-private partnerships) tourists were being convinced to spend their weekends in the notoriously seedy cities of Beacon and Poughkeepsie with the opening of several new museums and attractions, including the Walkway Over the Hudson mentioned in the opening to this article.

Steinhaus remains a controversial figure, both due to his merciless cuts to government and privatization but also on a personal level, often picking incredibly petty political fights or calling legislators into his office solely to berate them. With that said, in a moment of profound crisis he undeniably defined the role of the county executive, a position which in many peer counties is effectively relegated to rubber-stamping legislation and cutting ribbons. When he chose to retire after 20 years in office, Molinaro had the backing of all notable local Republicans before he even officially announced.

- Marc Molinaro, 2018 Republican nominee for Governor

It is somewhat implied when I describe his level of overperformance, but let’s make it explicit: people really like Marc Molinaro. Or at least, once did. This is a result both of his personability (particularly compared to Steinhaus, who won his narrowest victory of 3.3 points in his final 2007 race) and a legitimate track record of ideological moderation, particularly as he got deeper into his tenure as executive. He would win that office by 23.1 points in 2011, 26.5 in 2015, and 17.0 in 2019, a consequence of decreased ticket splitting in the Trump era. All this while Dutchess County narrowly backed Clinton in 2016 and delivered results 10 or more points worse for other Republicans seeking county office. In soliciting more bohemian audiences through tax breaks and other subsidies to art museums and other attractions, ironically the business-friendly Republicans who dominated Poughkeepsie and Beacon since the late 1800s very quickly rendered themselves extinct in the same timespan where Molinaro managed to stay comfortably above water.

In his time in the Assembly, Molinaro voted against charter schools and to end fracking. He emphasized addiction treatment, mental health, and disability rights in his time as executive, candidly speaking about his mother’s struggle with depression and his daughter’s special needs. While attending a Trump rally in Poughkeepsie before the New York primary (Molinaro made clear he was there in his capacity as executive, something I believe given he was at the Bernie rally in Poughkeepsie the week prior), he publicly announced he would not be voting for Donald Trump in 2016, instead writing in then-retiring Congressman Chris Gibson.

2018 saw Andrew Cuomo seeking his third term as governor. Son of another longtime governor, then Attorney General Cuomo won a decisive 30.5 point victory in a 2010 cycle otherwise filled with woe across the country for Democrats. He put down Zephyr Teachout’s Working Families Party backed challenge in 2014 as well as Westchester County Executive Astorino in the general election, and looked in pole position to do the same to Cynthia Nixon and the chosen Republican sacrificial lamb. The scandals that would undo him, long rumored and freely spoken of even in this period, would not come to a head for three more years. Expected challengers, John DeFrancisco, Joel Giambra, Brian Kolb, Joe Holland, all announced campaigns only to quietly withdraw. All but one. Marc Molinaro announced his campaign in Tivoli. Pinned to his lapel was the ‘60s cartoon character Underdog.

People liked Marc Molinaro, as I have said. But in order to like Molinaro, you have to know Molinaro. Dutchess is the 15th most populous county in New York State with a population of about 295,000. Columbia County, which Molinaro represented portions of in the Assembly, is 40th at just over 60,000 residents. Outside of Dutchess County and state Republican circles, few knew who Marc Molinaro even was.

As the presumptive nominee well before the election, Molinaro was able to raise the largest haul of his career by far, $2.41 million dollars in the course of the campaign. Andrew Cuomo in the same period raised $37 million, actually down from his 2014 campaign’s $48 million as donors found more interesting attractions in the House and Senate. Molinaro’s longstanding discomfort with fundraising persisted into this higher echelon, with him even calling it “unseemly.” “I’ve always had that feeling that I’m on the outside. I just have,” he said in a Times interview. “I know a lot of people who feel that way. But when I’m in a room with exceptionally wealthy people, I feel like I’m the poor kid.”

Molinaro’s strategy is a bit novel today, as he actually seemed to run a fairly nonpartisan, reform-minded race against Cuomo. He backchanneled to try and get SDNY U.S. Attorney and Cuomo critic Preet Bharara to run as a Democrat and Republican for Attorney General, creating something of an anti-corruption fusion ticket between the two. There is no indication anyone but Molinaro took this seriously. He ran on instituting campaign finance reforms, chided Cuomo for the dysfunction of the MTA, criticized the Trump tax cuts, frankly his lines of attack were not much different from what was being said by Cynthia Nixon or the Green Party’s Howie Hawkins.

Cuomo for his part mostly ignored Molinaro, banking on the environment of the first Trump midterm and in their one debate calling Molinaro a “Trump mini-me,” backing it up with Molinaro’s vote against gay marriage in the Assembly and pro-life views. Molinaro challenged Cuomo to more debates, even attending an undercard debate with only third party candidates, but simply was not given any further oxygen. Andrew Cuomo was re-elected by 23.4 points.

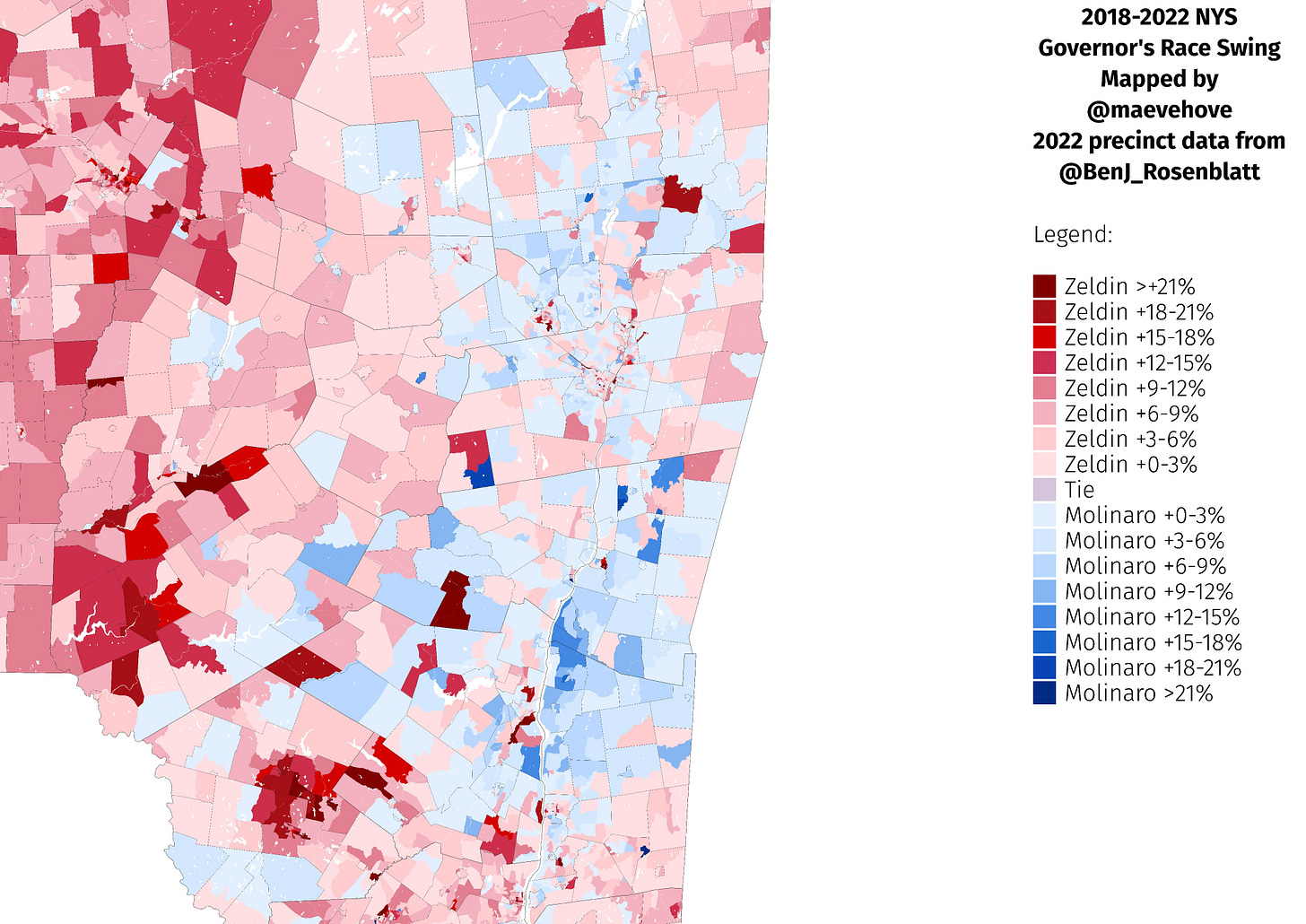

In 2022, the next Republican nominee, Lee Zeldin only lost by 6.4 points. This alone would seem to indict Molinaro’s run, not only did he lose by a large margin, but it was proven the very next cycle that a Republican could come far closer in New York State. Let’s not be so hasty for a moment.

This is a swing map I made of those two governor’s races about a year ago. In red are areas where Lee Zeldin performed better than Marc Molinaro. In blue are areas where Marc Molinaro proved stronger. Despite an 18 point difference, there remains a lot of blue on this map upstate.

In the Mid-Hudson and the Capital District, Zeldin at best pulled about even with Molinaro. In fact in his home turf of northern Dutchess and Columbia counties, Molinaro did anywhere from 5-15 points better than Zeldin. In the scope of a midterm with an unpopular president of your own party, against an entrenched popular incumbent with a war chest about 15x larger, this is fairly impressive.

Zeldin was able to dramatically improve on Molinaro’s margin in 2022 in New York City, the most expensive media market in the country where Governor Cuomo was raised, but was relatively alien to Governor Hochul. This was as much a function of genuine swing in the vote as it was depressed Democratic turnout.

Between 2018, the midterm of an unpopular Republican president, and 2022, the midterm of an unpopular Democratic President, turnout fell dramatically in more Democratic areas of the state and rose accordingly in more Republican areas of the state. This happened so linearly that despite turnout being near in each election, 48.0% in 2018 and 47.7% in 2022, most precincts in New York City experienced double-digit fluctuations in turnout, almost exclusively to Zeldin’s benefit.

To compare these two races is quite apples to oranges, given how profoundly different the national and statewide environment was in each. What we can say confidently though is that Molinaro gave a rather strong performance on his home turf, in some counties the best for a statewide Republican since George Pataki. It would also however be the apparent peak of his electoral prowess. Under the future lines of his congressional seat where he eeked out a 1.6 point win in November 2022, he beat Cuomo by 4.5.

If we judge Marc Molinaro’s gubernatorial run at its most basic, how close he came to winning, he failed entirely. If we ask if he increased his profile in the Mid-Hudson Valley and the Southern Tier for further career advances, we may come to a different conclusion.

“As we look forward, every midterm election is a referendum on the party in power.”

- Molinaro’s concession statement after the August 2022 NY-19 special election

Molinaro took his loss in stride, perhaps because of the fact it was obvious the tiny window for an upset victory was completely sealed months before votes were cast. Marc Molinaro would not be a Governor, or a Senator, or otherwise hold statewide office. Despite this, he came out the other end of this race a rising star in Republican circles statewide and talk that had persisted for years of the next, most obvious direction for career advancement quickly hit a boiling point.

While Molinaro carried New York’s 19th Congressional District against Cuomo by a commanding 11.1 points, John Faso, the incumbent Republican in that seat handpicked by Chris Gibson to succeed him, fell to his challenger Antonio Delgado by 5.3 points. For the first time in his career, there were no rings to kiss, no clear line of succession for the congressional seat he had no doubt eyed since he was a teenager. 2020 however would see an unpopular Trump at the top of the ticket, so Molinaro would quietly inform the local GOP he wasn’t interested.

If there was a “surplus moment” for Molinaro in his time as executive, some tenure-defining crisis, it was likely the COVID-19 pandemic. When cases began being reported in New York State, Molinaro declared a state of emergency and instituted a lockdown on March 13th. Andrew Cuomo, Bill de Blasio, and the vast majority of New York counties would not issue similar orders for another three days.

In a time of surface-level national unity, when people acted calmed by Andrew Cuomo and the unprecedented state of lockdown was not yet met by public backlash, Molinaro joined the ranks of those affected in the worst of ways. His father Anthony, a sometimes distant figure in his life who was put on a ventilator at Westchester Medical Center only two days earlier, succumbed to the disease. Like the sons of others hospitalized in that period, he was not permitted to visit his bedside as he laid dying. Molinaro ended an interview shortly after with a note of caution and a plea to the public. "We all have a role in this. If we all hunker down just a little longer, if we engage in the distancing just a little bit longer, we'll slow the spread.”

Trump lost, Cuomo’s scandals were finally at the front of public discourse, and Biden’s approval rating was nosediving by the fall of 2021. From a farm in Rhinebeck, Marc Molinaro announced a campaign decades in the making: he would run for Congress against Antonio Delgado. From that very press conference he was striking several very Molinaro chords, insistence his opponent was a good guy and that said good guy was a puppet of monied Democratic donors who was distracted from doing better, as vague as that “better” is:

“The truth is, I don’t dislike our member of Congress, I don’t. I just don’t think he’s interested in taking up this most historic challenge, he’s more interested in mastering the Washington two-step, the dance with the donors, the PACs, the billionaires and the special interests, raising millions of dollars— just as Andrew Cuomo did— than engaging in the heavy lifting, the courageous advocacy and the day-to-day work of skillfully making a difference at home.”

It was fairly obvious foreshadowing that this race would be a continuation of how Molinaro ran all his races, (though in 2018 his sincere scorn of Cuomo was palpable) as the folksy, kid mayor who wasn’t born into privilege and didn’t have D.C. political consultants focus grouping what color shirt he should wear. This race however would not come to fruition.

In the chaos of the first few months post-Cuomo, Kathy Hochul’s first lieutenant governor found himself in a predicament four of his last seven predecessors (and recently another alum of the infamous 2009 State Senate) also experienced: federal indictment. It would be unfair to say that Delgado, an electoral overperformer in his own right, accepted the job because he was destined to lose to Molinaro, but no doubt daydreaming in the State Capitol was a safer bet.

This set up an August 2022 special election for the old bounds of the seat, with Ulster County Executive Pat Ryan chosen as his opponent. Ryan is something of an anti-Molinaro, a figure who besides the shared ambition and growing up just across the Hudson in Kingston is different in just about every way.

Son of the CEO of a local insurance company, Ryan was an intelligence officer in the U.S. Army during the Iraq War. Returning from duty, he became an executive in several data analytics firms, most recently one hilariously called “Dataminr.” While not living in the Hudson Valley since West Point, Ryan nonetheless found his way back from Brooklyn Heights (as many a pol has done) in time to participate in the swing seat’s congressional primary in the Trump midterm, already expected to be a wave year for Democrats. Ryan would get 17.9% in the crowded field, a second place finish bested by Delgado’s 22.1% in a deeply divided field. Afterward he mulled around til he was chosen to be the nominee for Ulster County Executive at a party convention, and now would have his second shot to fall upwards without any input from primary voters.

From the jump in this race, it was fairly obvious who had the advantage. Molinaro was a well-known figure in the district’s most populous county, had won it by a vast margin in his gubernatorial race, and had apparently scared Delgado (who won the district by an even larger 11.6 points in the 2020 election) out of the race. Polling quickly confirmed this, while no nonpartisan polling was conducted of the race, Molinaro held commanding leads in both Democratic and Republican-sponsored polls.

Pat Ryan however did have one thing on his side: the Supreme Court. About a month after Delgado’s resignation, the Supreme Court officially overturned Roe vs Wade, one of the effects of which was dramatic Democratic overperformance in a series of special elections. Though not yet winning any of them, (while the Alaska special election had occurred, the results of the final ballot were not tabulated until August 31st) there was certainly sound evidence behind the theory that Ryan may overperform in the post-Roe national environment, even as Molinaro’s campaign cruised into the special election saving money for the general, spending only $994k of $1.54 million dollars raised compared to Ryan’s war chest which was practically depleted by election day, $1.26M out of $1.58M raised spent on just the special election.

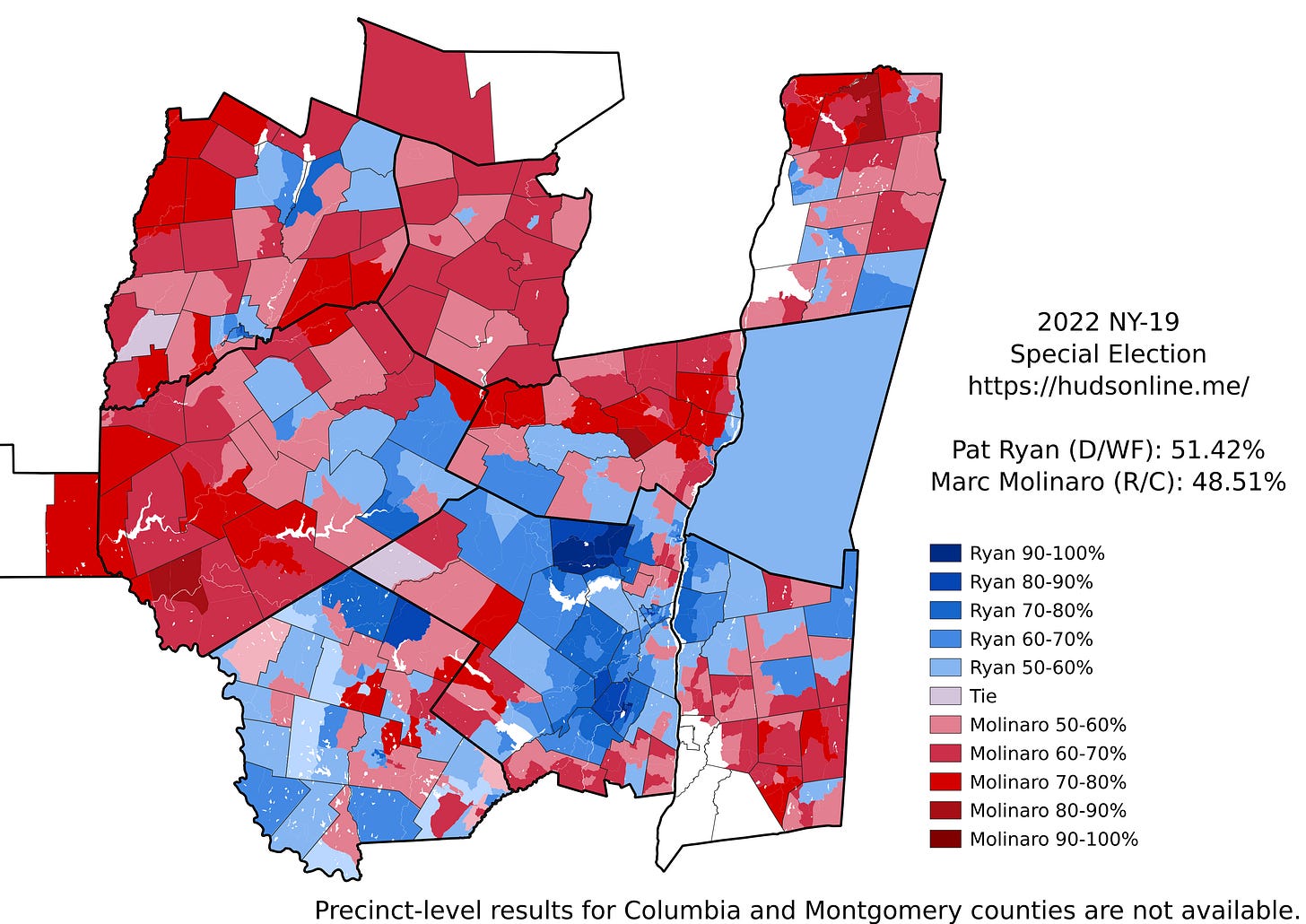

It is worth backtracking at this moment to examine that 2018 governor’s race under these same bounds. It is mapped below:

Molinaro did not just win, it was a true rout. He carried the district by 11.11 points. Even if one was to assume all third party voters preferred Cuomo to him (an unlikely prospect given they were all basically anti-Cuomo protest votes), he wins by 6.02 points. He carried every county but increasingly blue Ulster, and even there Cuomo was held to barely over 50% of the vote. Even Columbia County, home to a plethora of NYC country homes and the tourist traps of Hudson, went narrowly to Molinaro, the last time a Republican would win this county.

This is a sizable mandate, one that lead to many observers (including me, just outside the district in Poughkeepsie) writing it off entirely. Molinaro would be elected to Congress, find himself in a tougher but still manageable fight in November, and would hopefully be swept from office in the coming presidential year or a second Trump midterm. This is not what happened.

Marc Molinaro lost, and he lost in rather spectacular fashion. Compared to his 2018 run, the floor fell out practically everywhere, with his few areas of substantial improvement being stray fragments of exurban southern Dutchess and the one seasonal, now increasingly permanent presences of the Satmar and Vizhnitz Hasidic dynasties in Sullivan County.

Perhaps nowhere was his collapse in regional goodwill more gruelling than in his own Tivoli and Red Hook. Increasingly blue Tivoli and the larger town of Red Hook, which Molinaro by now had moved just outside village limits to, did not back him in 2018, but it was kept admirable for a Republican in the environment of the Trump midterm. Cuomo took 60.56% of the vote in Tivoli to Molinaro’s 34.34%, and the larger town of Red Hook went 51.35%-44.92% for Cuomo. While town-by-town data is not available, Molinaro likely proceeded to win Red Hook decisively in his final 2019 race for county executive, as he had in every previous election of his career. In this special election, Pat Ryan got 71.39% of the vote in Tivoli to Molinaro’s 28.61%. In wider Red Hook, Ryan got 60.99% to Molinaro’s 38.93%. The town that birthed his career and granted him an improbable ticket to the State Assembly had utterly excoriated him.

Ryan’s victory has been described as an upset, and in many ways it is, but I do think it is worth some differentiation from other special elections in this period that went favorably for Democrats. Of all special elections between the Supreme Court overturning Roe and the general election, this was the only race to show a significant swing towards the Republican. Delgado was a significant overperformer in his own right as already mentioned, and got a far more decisive victory against his previous opponent.

Molinaro flipped the most populous county of Dutchess from blue to red, as well as Sullivan, Otsego, and Rensselaer. Ryan meanwhile only kept the counties of Ulster and Columbia in the Democratic column, though kept the floor from falling out in them enough to eeke out a victory. A narrative has been formed since of Ryan’s electoral prowess, particularly as the only Democrat to keep control of a swing seat through the Zeldin wave (a feat which as I will document in a future article, is far less substantial than it initially seems). The evidence to me does not indicate Ryan is any better than a replacement-level generic Democrat. This race was only an upset in the context of Molinaro’s presumed electoral prowess, electoral prowess which at the federal level all but evaporated.

- Josh Riley, Democratic nominee against Molinaro in 2022 and 2024

Molinaro played it very safe in his special election campaign, not just financially but politically. He stuck to the familiar playbook he had been true to since the beginning of his career. Stick to what everyone can agree on, the economy must grow, crime must be brought down, mental health is important, corruption is bad. When your opponent tries to bring it to more lightning rod issues like abortion or Trump, dodge or hedge everything through a lens of “I understand everyone has very strong opinions on this subject.”

This is fine as an executive, not really as a legislator. There is a reason prior to his tenure in Congress, what haunted Molinaro most was his vote against gay marriage in the State Assembly. To be a legislator is to make binary yes or no votes (and the occasional abstention) on the most hot-button of issues. One may be able to vote their district at times, but these times are fewer and far between the smaller their party’s majority in that body is. People voted for Ryan because they knew what Ryan stood for on those decisive issues.

When I listen to left-of-center people in my life who were vaguely supportive of Molinaro as executive speak of him now, it is as if he made a heel turn like a WWE wrestler. That the longtime respectable moderate just flipped on a dime to take up a flurry of right wing culture war issues. Only Marc Molinaro knows if his views cynically changed, or if he always held such beliefs and kept them out of the limelight.

But what I suspect became clear to Molinaro in this period is that he could not climb any higher while avoiding these issues. As executive, he was a figure of consensus whose main responsibility was promoting economic development, hardly controversial as a generality. This role and his personability gave him a lot of cross-party supporters, which he thought would carry over to the Congressional level. But if what he wanted was a swing seat with an R next to his name, those same voters who supported him for office since he was a teenager would never tolerate him. Molinaro would have to appeal to a much smaller, more ideologically stratified base than he ever had in the past. As his rhetoric evolved, his fundraising rose accordingly.

Molinaro’s opponent in the general election due to a chaotic redistricting process would not be now incumbent Congressman Pat Ryan, but instead a nice set of teeth with a Harvard Law degree named Josh Riley. The bounds of the district too would change dramatically with a last minute court order to redraw lines that once included Red Hook, now excluding all of his native Dutchess County and stretching all the way to Ithaca. Riley, who moved back to the district from Washington D.C. for the first time since high school to run for the seat, was quick to decry Molinaro as a carpetbagger. Molinaro meanwhile quietly moved his family to Catskill, about a 15-minute drive from his previous home.

You may be getting the impression I do not see Riley as a particularly impressive opponent to Molinaro, and I can’t really deny that. I’ve written about him before in a previous piece that I prefer to not parrot, though someone else has. Every part of a multimillionaire D.C. lawyer moving back to dress like a lumberjack and run a folksy, everyman campaign against a “do-nothing career politician” who at least had the grace to stick around is at best farcical, at worst deeply offensive. That said, for some bizarre reason it seems to be the playbook the DCCC’s consultants feel most confident in. Should he lose this cycle, there are several far more honest and experienced candidates testing the waters.

The fact he was running against such a caricature however makes Molinaro’s narrow victory that November even more staggering.

Molinaro won by a mere 1.56 points in a district he carried by 4.59 in the 2018 gubernatorial race. In an even larger rebuke, Molinaro significantly underperformed Lee Zeldin on the same ballot who won by 6.73 points, a whole 5.14 points better than Molinaro. This was most apparent in the western end of the district, where Molinaro did in many cities and towns as much as 10-20 points worse than Zeldin.

The special election proved to not be a fluke. Molinaro’s days of overperformance are over. Narrow or not, Molinaro was going to be a frontline member of the smallest Republican majority in congressional history.

“If he wasn’t always on TV, I couldn’t pick him out of a lineup.”

- Unnamed House Democrat on background

I feel a certain kinship with Marc Molinaro. We were both raised in Dutchess County by single mothers, both attended the same community college, both Pell Grant recipients, and both became deeply involved in politics as teenagers because of formative, dare I say traumatic memories of the precarity of our early lives and how public policy intersected. It instills a certain drive in understanding how those realities hold us back to persevere despite them, though we came to very different ideological conclusions, and I’m taking a bit longer to find my footing.

I always figured Molinaro would run for Congress at some point, probably win, but even I have to admit I expected him to be something more of New York’s Brian Fitzpatrick, a moderate Republican in a swing or even generally Democratic seat. This has not been how he has legislated. Molinaro was pivotal to the ascention of Mike Johnson to the speakership, giving an impassioned speech in a caucus meeting, imploring his colleagues to end the chaos by empowering one of the most right-wing members of their conference. As much as I had always rolled my eyes at this idea Molinaro just governed by consensus and was one of the good Republicans, even to me his time in the House so far has been quite jarring.

Molinaro has at times lightly bucked the general party line, such as on certain appropriation bills and labor issues. But in general, he has been a reliable vote for Mike Johnson. Molinaro, who publicly boasted he did not vote for Donald Trump in 2016, endorsed Trump this March. While Molinaro did not travel to Nassau County this week for his second Trump rally, he did get a mention. Sandwiched in a 30-second tranche of other brief quips which amounted to the totality of Trump’s discussion of the many swing races on the ballot in November, Trump threw in “Marc Molinaro— great.”

District lines were humbly adjusted by the state legislature, something which has been a boon to Molinaro who has lost the dark blue vote sink of Woodstock in exchange for some red parts of metro Albany and other more favorable areas. From Molinaro’s 1.56 point victory in 2022, he will find himself now running in a district which voted for congressional Republicans by 5.25 points that same cycle.

We are very far into this piece for what may seem the most obvious question. Will he win? Perhaps I have clickbaited a bit at the beginning because I believe the most likely answer is yes. Molinaro’s new district voted very narrowly for Biden in 2020, 49.64% to Trump’s 48.22%. A certain amount of energy has been injected into the race with Kamala Harris’ nomination and as always affluent left-wingers have bought country homes, but with Riley as the nominee against the now-incumbent, it seems to me an uphill battle. With that said, I would still handicap the race at 1 in 3 odds Riley wins. If he doesn’t, Molinaro is intensely vulnerable to being swept out of office in a wave year, particularly against a candidate who also has some time in lower elected office under her belt. The man who has spent over his entire adult life in elected office will likely find himself out of a job this decade.

Marc Molinaro has chosen his path. Last year, Molinaro’s anointed successor for Dutchess County Executive, Sue Serino, won by 13.28 points, a smaller margin than Molinaro’s last win but decisive evidence that even conscious of changing political tides in Dutchess County, he likely could have held onto his post for several more terms, maybe even decades, outdoing that 20 year record set by Bill Steinhaus. In being a local position only elected on off years, Molinaro had plenty of opportunities to raise his profile by running in other statewide contests as his 2018 governor’s run without risk of losing that dependable post. Should he lose his seat he will find himself a resident not of Dutchess but Greene County, a much smaller, unfamiliar pond with under 50,000 residents (though among them, dozens of my second and third cousins who will reliably vote for him in November and beyond). Even if he returned to Dutchess, another longtime popular pol now holds the highest office attainable and shows no signs of wanting to part with it. But Molinaro did not want to be a mere county executive for life, he wanted to be Governor, Senator, President— but would settle for Congressman. An office in Washington is what the kid mayor always desired, not one in Poughkeepsie, though said Washington office may be slightly less opulent than he once dreamed.

This is Molinaro’s gambit. In November 2024, and perhaps November 2026 or 2028, Marc Molinaro will not only be fighting for his congressional seat: he will be fighting for the storied career that has been the only one he has known since he was a teenager. A candle which has had a reliable slow burn, but to all conscious observers looks about to run out of wick.